MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON . BOMBAY . CALCUTTA . MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK . BOSTON . CHICAGO

DALLAS . SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

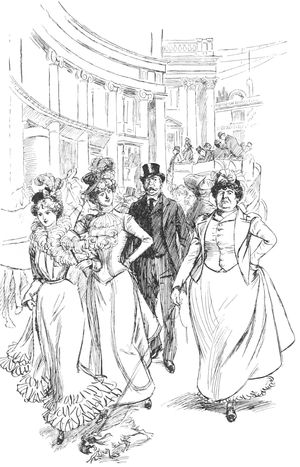

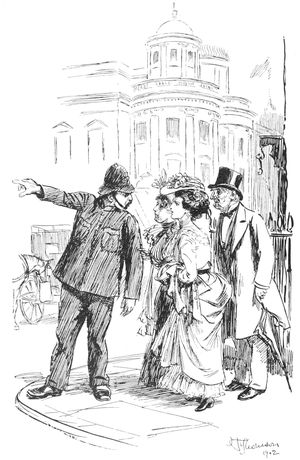

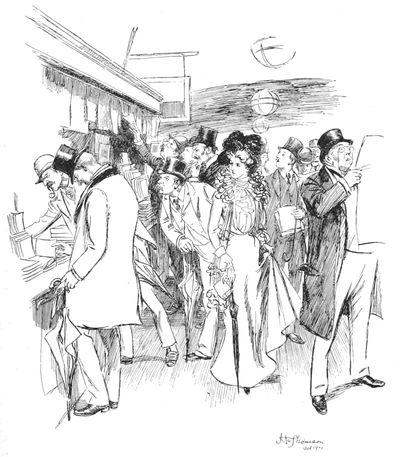

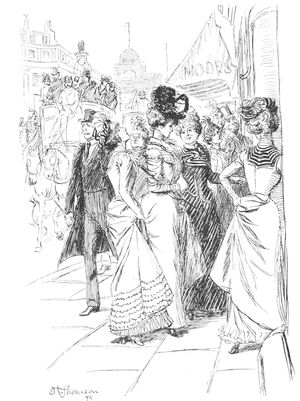

Crossing at Piccadilly Circus.

BY MRS. E. T. COOK

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

HUGH THOMSON AND

F. L. GRIGGS

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON

1920

COPYRIGHT.

First Edition, 1902.

Reprinted, 1903, 1907, 1911, 1920.

CHAPTER I PAGE

HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS 1

CHAPTER II

THE RIVER 22

CHAPTER III

RAMBLES IN THE CITY 53

CHAPTER IV

ST. PAUL'S AND ITS PRECINCTS 84

CHAPTER V

THE TOWER 100

SOUTHWARK, OLD AND NEW 121

CHAPTER VII

THE INNS OF COURT 137

CHAPTER VIII

THE EAST AND THE WEST 162

CHAPTER IX

WESTMINSTER 187

CHAPTER X

KENSINGTON AND CHELSEA 210

CHAPTER XI

BLOOMSBURY 238

CHAPTER XII

THEATRICAL AND FOREIGN LONDON 273

LONDON SHOPS AND MARKETS 298

CHAPTER XIV

THE GALLERIES, MUSEUMS, AND COLLECTIONS 324

CHAPTER XV

HISTORIC HOUSES AND THEIR TENANTS 358

CHAPTER XVI

RUS IN URBE 385

CHAPTER XVII

THE WAYS OF LONDONERS 414

CHAPTER XVIII

THE STONES OF LONDON 447

INDEX 473

PAGE

CROSSING AT PICCADILLY CIRCUS Frontispiece

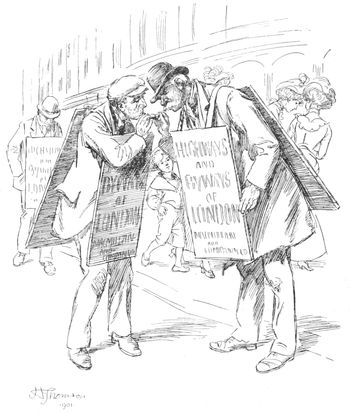

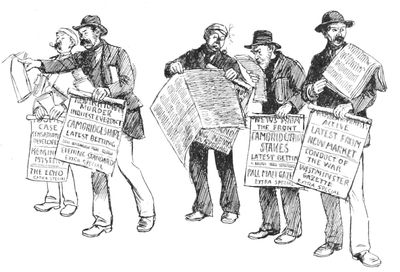

SANDWICH-BOARD MEN 6

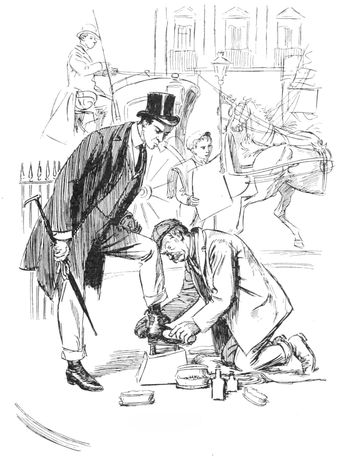

THE SHOEBLACK 11

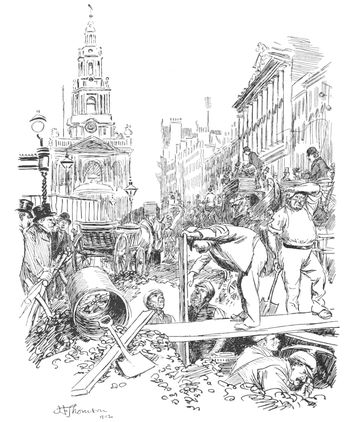

WHEN THE STRAND IS UP 16

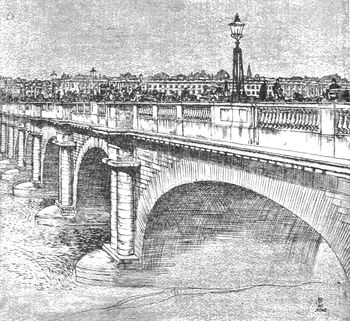

WATERLOO BRIDGE 22

SIGHTSEERS 34

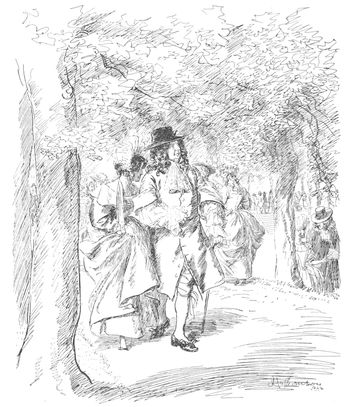

THE "TOP" SEASON 40

AN UNDERGROUND STATION 53

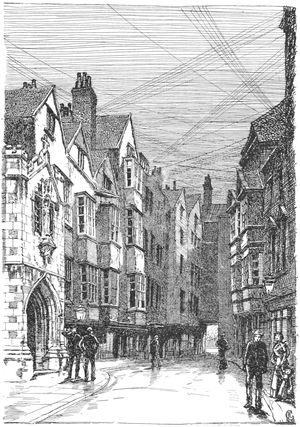

CLOTHFAIR 57

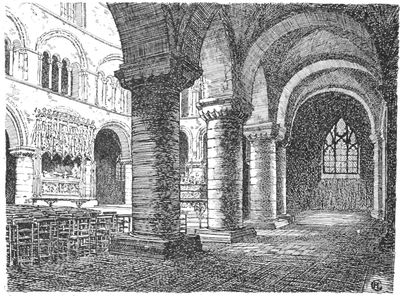

ST. BARTHOLOMEW'S, SMITHFIELD 66

FIGHTING COCKS 85

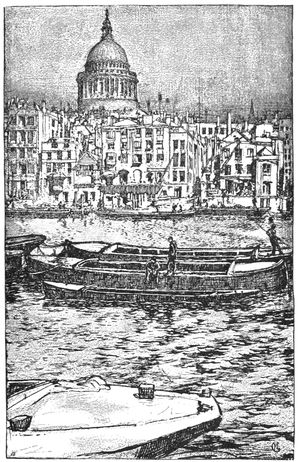

ST. PAUL'S FROM THE RIVER 87

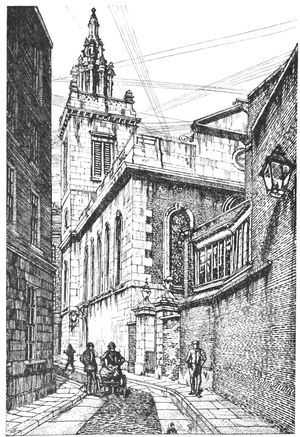

ST. MICHAEL'S, PATERNOSTER ROYAL 96

(p. xii) A BEEFEATER 102

CRICKET IN THE STREET. THE LOST BALL 127

A COUNTY COURT 130

PEPYS AND HIS WIFE 140

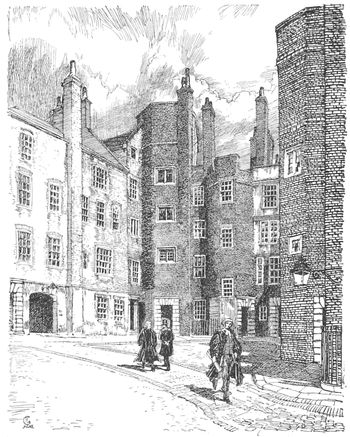

LINCOLN'S INN 152

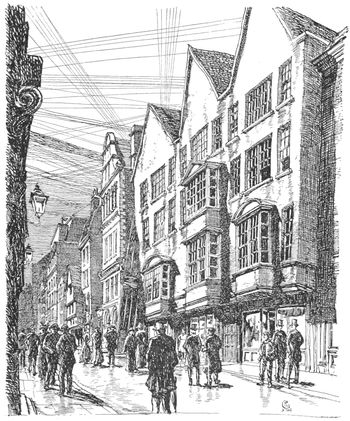

FETTER LANE 157

A RAILWAY BOOKSTALL 163

THE CITY TRAIN 165

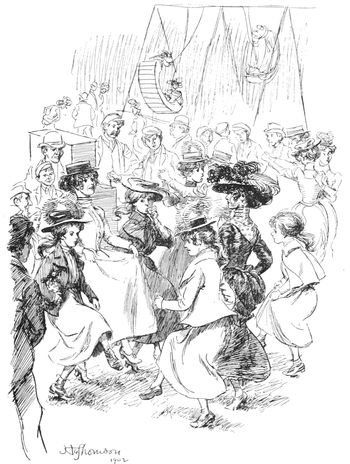

BANK HOLIDAY 171

IN REGENT STREET 180

PICCADILLY 182

SPESHUL! 187

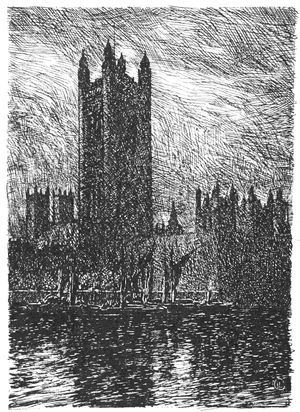

VICTORIA TOWER, WESTMINSTER 206

ANGLERS IN THE PARKS 211

KENSINGTON PALACE AND THE ROUND POND 214

EARL'S COURT 221

THE GERMAN BAND 239

THE PAVEMENT ARTIST 249

MUDIE'S 267

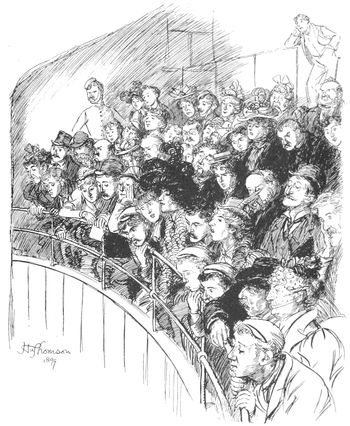

THE "GODS" 281

(p. xiii) ICE-CREAM BARROW 291

THE ORGAN-GRINDER 293

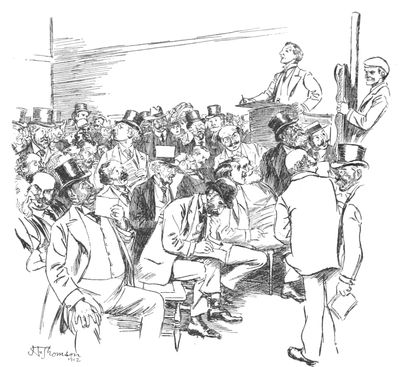

A SALE AT CHRISTIE'S 298

THE DOG FANCIER!!! 304

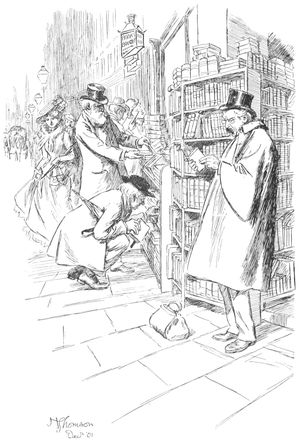

IN THE CHARING CROSS ROAD 306

SATURDAY NIGHT SHOPPING 313

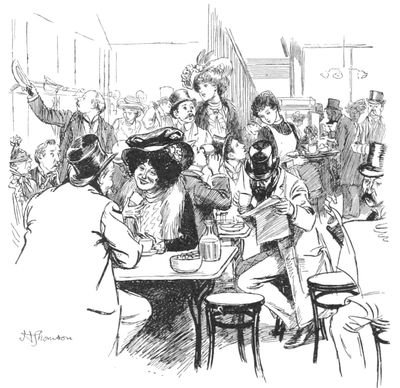

AN AERATED BREAD SHOP 321

A SKETCH IN TRAFALGAR SQUARE 325

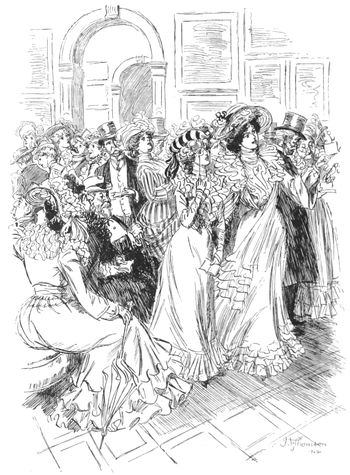

AT THE ROYAL ACADEMY 339

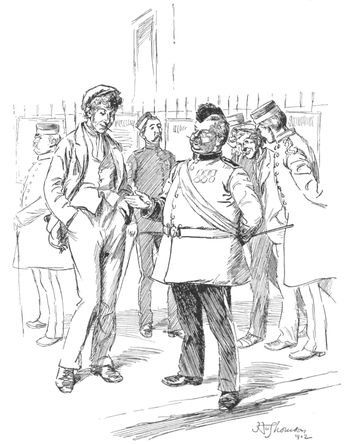

RECRUITING SERJEANTS BY THE NATIONAL GALLERY 345

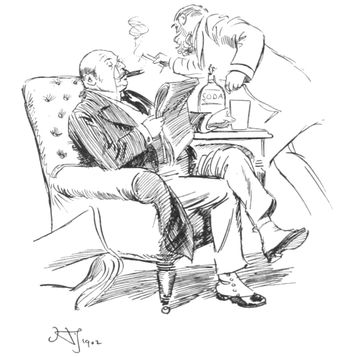

AT THE CLUB 359

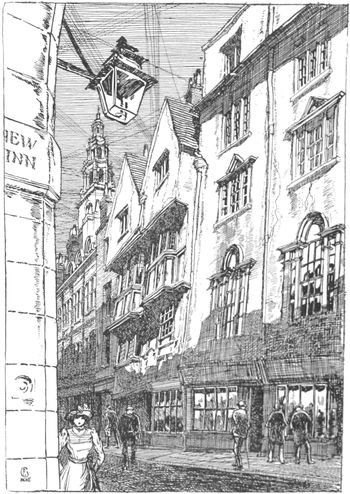

WYCH STREET 365

CRICKET IN THE PARKS 385

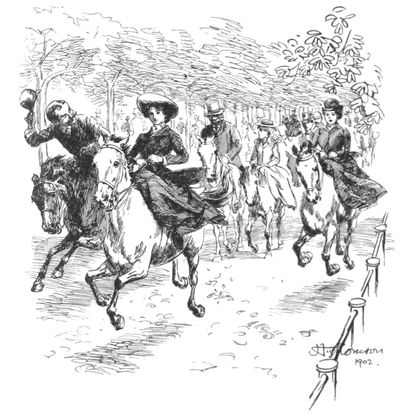

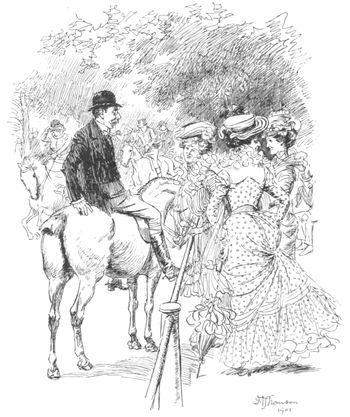

ROTTEN ROW 389

ROTTEN ROW 391

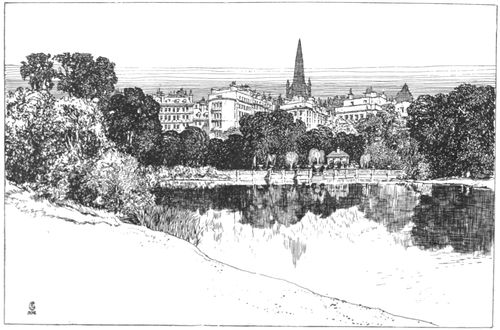

THE SERPENTINE, HYDE PARK 393

TEA IN KENSINGTON GARDENS 396

A FOUNTAIN IN ST. JAMES'S PARK 398

THE REFORMER 403

A JURY 414

(p. xiv) 'BUS DRIVER 415

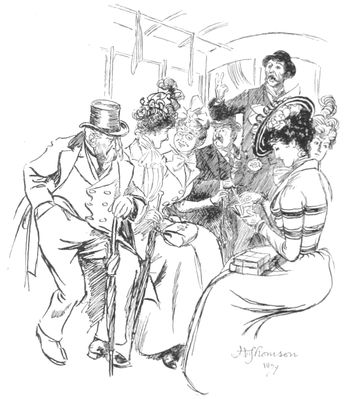

INSIDE 419

"BENK, BENK!!" 421

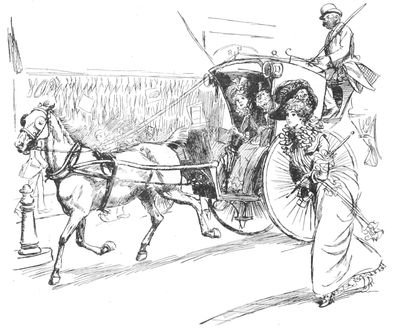

THE HANSOM 424

A DOORSTEP PARTY 428

HOP-SCOTCH 433

THE RETURN, BANK HOLIDAY 435

FLOWER GIRLS 438

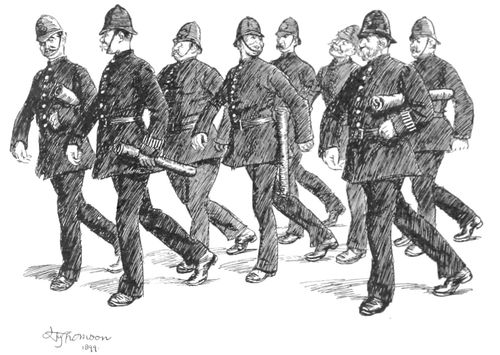

THE MEN IN BLUE 447

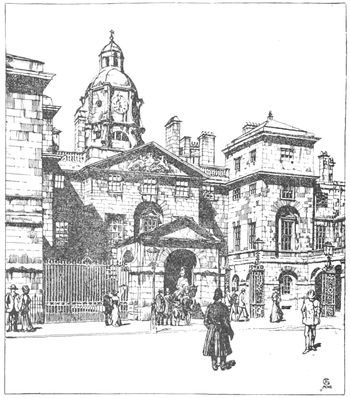

THE HORSE GUARDS 456

(p. xv) "I confess that I never think of London, which I love, without thinking of that palace which David built for Bathsheba, sitting in hearing of one hundred streams,—streams of thought, of intelligence, of activity. One other thing about London impresses me beyond any other sound I have ever heard, and that is the low, unceasing roar one hears always in the air; it is not a mere accident, like a tempest or a cataract, but it is impressive, because it always indicates human will, and impulse, and conscious movement; and I confess that when I hear it I almost feel as if I were listening to the roaring loom of time."—Lowell.

"London: that great sea whose ebb and flow

At once is deaf and loud, and on the shore

Vomits its wrecks, and still howls on for more,

Yet in its depths what treasures!"—Shelley.

"Citizens of no mean city."

The history of London is—as was that of Rome in ancient times—the history of the whole civilised world. For, the comparatively small area of earth on which our city is built has, for the last thousand years at least, been all-important in the story of nations. Its chronicles are already so vast that no ordinary library could hope to contain all of them. And what will the history of London be to the student, say, of the year 3000 A.D., when our present day politics, our feelings, our views, have been "rolled round," once more, in "earth's diurnal force," and assume, at last, their fair and true proportions?

In "this northern island, sundered once from all the human (p. 2) race," has for centuries been lit one of the torches that have illumined humanity. Not even Imperial Rome shone with such a lustre; not even the Cæsars in all their purple ruled over such a mighty, such an all-embracing empire.

The history of this mighty empire is bound up with the history of London. For, the history of London is that of England; it was the river, our "Father Thames"—her first and most important highway, a "highway of the nations,"—that brought her from the beginning all her fame and all her glory. Partly by geographical position, partly by ever-increasing political freedom, and partly, no doubt, by the efforts of a dominant race, that glory has, through the centuries, been maintained and aggrandised.

And why, some may ask, is London what it is? Why was this spot specially chosen as the capital? Surrounded by marshes in early Roman times, periodically inundated by its tidal river, densely wooded beyond its marshes, it can hardly have seemed, in the beginning, an ideal site. Why was not Winchester—so important in Roman times, and, later, the capital of Wessex—preferred? Why were not Southampton or Bristol—apparently equally well placed for trade—favoured? We cannot tell. The site may have been chosen by Roman London because it was the most convenient point for passing, and guarding, the ferry or bridge over the Thames, and for keeping up the direct communication between the more northerly cities of Britain, and Rome. Or, the nearer proximity to the large Continent, the better conditions for trade offered by the wide estuary of the Thames, possibly account for London's supremacy.

The early Roman city on this time-honoured site, the poetically named "Augusta,"—that replaced the primitive British village—flourished greatly in the early days of the Christian era, and was large and populous; though the Romans did not consider it their capital, and never—we know not why—created it a "municipium," like Eboracum (York), or Verulamium. It (p. 3) was founded some time after the visit of Julius Cæsar to Britain, B.C. 54, and it occupied a good deal of the area of the present City, extending, however, towards the east as far as the Tower, and bounded on the west by the present Newgate. The old Roman fort stood above the Wallbrook. Here in old days ran a stream of that name, long fouled, diverted, forgotten, and, like the Fleet River, only now remembered by the name given to its ancient haunt. The city of Augusta—or Londinium as Tacitus calls it—has left us hardly a trace of its undoubted splendour. In London, ever living, relics of the past are hard to find. The lapse of centuries has deeply covered the old Roman city level, and what Roman remains exist are generally discovered, either in the muddy bed of the Thames, or at a depth of some twelve to nineteen feet below the present street. Of Roman London there is scarce a trace—a few meagre relics in Museums, a few ancient roots of names still existing, an old bath, traces of a crumbling wall, the fragment that we call "London Stone," the locality of Leadenhall Market (undoubtedly an old "Forum"), and a portion of the old Roman Way of "Watling Street"—the ancient highway from London to Dover—running parallel with noisy Cannon Street.

All this seems, perhaps, little when we think of the undoubted wealth and power of the old "Londinium," or "Augusta." But it has always been the city's fate to have its Past overgrown and stifled by the enthralling energy and life of its Present. It is as a hive that has never been emptied of its successive swarms. This is, more or less, the fate of all towns that "live." The Roman town was, of course, strongly walled, and the names of its gates have descended to us in the present "Ludgate," "Moorgate," "Billingsgate," "Aldgate," &c.—names very familiar to us children of a later age—and now mainly associated with the more prosaic stations on the Underground Railway! Nevertheless, prosaic as they are, these stations commemorate the old localities. Roman London was at no time large in circumference, extending only from the Tower to (p. 4) Aldgate on one side, from the Thames to London Wall on the other. And when the Romans left, and the Saxons, after a brief interval, took their place, the city still did not grow much larger, nor did the blue-eyed and fair-haired invaders contribute much to the decaying fortifications; though it is said that King Alfred—he whose "millenary" we have recently commemorated—restored the walls and the city as a defence against the ravages of the Danes. Saxon London, however, which in its time flourished exceedingly, and existed for some 400 years, is, so far as we are concerned, more dead even than Roman London. Successive fire and ravage have obliterated all traces of it. Norman London, which after the Conquest replaced Saxon London, did not, apparently, differ greatly in externals from its predecessor. The churches were now mainly built of stone, but the picturesque houses were, as we know, despite successive destroying fires, still constructed of wood. From Norman London, we retain the "White Tower,"—that picturesque "keep" of London's ancient fortress—the crypt of Bow Church, and that of St. John's, Clerkenwell, with part of the churches of St. Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield, and St. Ethelburga, Bishopsgate. Little escaped the many great fires that in early times devastated the city.

As for the ancient highways of London, very possibly these did not differ greatly in their course from our modern ones; for the Anglo-Saxon race has always been very conservative in rebuilding its new streets, regardless of symmetry or directness, on the lines of the destroyed ones. At any rate, we know that the original church of St. Paul's—the first of three built on this site, founded by Ethelbert about the year 610—and that of Westminster—altered, rebuilt, and enlarged by successive kings—must have early sanctified these spots, and necessitated thoroughfares between the two. Nay, even in Roman times, temples of Diana and Apollo are believed to have adorned these historic sites. It is strange, indeed, that the old, long-vanished Roman wall, pierced only by a few gates, (p. 5) and the ancient street-plans laid down by the Roman road surveyor, should still keep modern traffic more or less to the old lines. A few new streets have recently been made from north to south, but still the main traffic goes from east to west, owing to the paucity of intersecting thoroughfares. The city of London, as laid out in Roman times, remained, through Saxon and Norman dominion, practically of the same extent and plan as late as the time of Elizabeth, in whose reign there were as many houses within the city walls as without them. Roman influence is still dominant in modern London. The large block of ground without carriage-way about Austin Friars is a consequence of the old Roman wall having afforded no passage. And possibly many of the narrow, jostling City streets have in their day reflected the shade and sun of Roman "insulas," each with its surrounding shops, just as, later, their dimensions may have shrunk between the overhanging, high-gabled houses of Tudor times, to widen again under the tall Stuart palaces of the Restoration.

Sandwich-board Men.

The high antiquity and conservatism of London are shown in nothing more than in these narrow, crooked streets—streets so different from those of any other big metropolis—streets that our American cousins, in all the superiority of their regular "block" system, permit themselves to jeer at! We know, however, little for certain of the actual topography of London streets, until the important publication of Ralph Aggas's map in 1563, soon after Elizabeth had begun to reign. This map of "Civitas Londinium" is strange enough to look at in our own day. Its main arteries are the same as ours: the ancient highway of the Strand is still the Strand; those of "Chepe" and "Fleete" still flourish; Oxford Street, then the "Oxford Road" and "The Waye to Uxbridge," ran between hedgerows and pastures, in which, according to Aggas, grotesque beasts sported; the thoroughfare of the "Hay Market,"—not yet, indeed, "a scene of revelry by night,"—curves between vast meadows, in one of which a woman of gigantic size appears to be engaged in (p. 6) spreading clothes to dry; Piccadilly, at what is now the "Circus," is merely called "The Waye to Redinge," and is innocently bordered by trees. In these infantine beginnings of the now populous "West End," there are, indeed, occasional plots occupied by "Mewes," but St. Martin's Church (then a small chapel) stands literally "in the Fields," and St. Martin's Lane is altogether rural. In a later map—one of the year 1610—the (p. 7) main arteries are still the same; but, though the town had grown rapidly with the growth of commerce in Elizabeth's reign, "London" and "Westminster" are still represented as two small neighbouring towns surrounded by rural meadows; while "Totten-court" is a distant country village, Kensington and "Marybone" are secluded hamlets, Clerkenwell and "St. Gylles" are altogether divided from the parent city by fields, and "Chelsey" is in the wilds.

It is strange that London fires—and London, in the middle ages, was specially prolific in fires—have never altered the course of the city's highways. Sir Christopher Wren wished, indeed, after the Great Fire of 1666, to be allowed to alter the plan of the desolated town and make it more symmetrically regular: with all due admiration of his genius, one cannot, however, help feeling a certain thankfulness that destiny averted his schemes, and that in the prosaic London of our own day we can still trace the splendour, the romance of its past. Thus, even in the grimy city "courts" we can still imagine a Roman "impluvium," or the ancient gardens of Plantagenet palaces; in the blind alleys of "Little Britain," the splendours of the merchants' mansions; in the ugly lines of mews and slums, the limits of the vanished Norman convent closes. The boundaries are still there, though nearly all else has gone. For, though Londoners are generally conservative with regard to their chief sites and the lines of their streets, they have, so far as their great buildings are concerned, always been by nature iconoclastic. Not that we of the present day need give ourselves any airs in this matter. Although, indeed, for the last half-century the spirit of antiquarian veneration has been abroad, yet the great majority of Londoners are hardly affected by it, and the pulling down of ancient buildings continues almost as gaily as ever at the present day. It may be said that we pull down for utilitarian reasons; well, so did our forefathers; Londoners have always been practical. Religious zeal may occasionally have served to whet their destructive (p. 8) powers, but the results are pretty much the same. Perhaps Henry VIII.—that Bluebeard head of the Church and State—has, in his general dissolution of the monasteries and alienation of their property, been the greatest iconoclast in English annals; yet even he must have been nearly equalled by the Lord Protector Cromwell, whose Puritanical train wrought so much havoc among London's monuments of a later age. Reforms and improvements, all through the world's history, have always been cruelly destructive. For, while churches and palaces were destroyed as relics of Popery, while works of art were demolished, and frescoes whitewashed in reforming zeal, fresh life was always sprouting, fresh energy ever filling up gaps, ever obliterating the traces of the past, the relics of the older time. Sir Walter Besant, in his picturesque and vivid sketch of English history, has realised well for us the city's past life:—

"It is (he says of the Reformation) at first hard to understand how there should have been, even among the baser sort, so little reverence for the past, so little regard for art; that these treasure-houses of precious marbles and rare carvings should have been rifled and destroyed without raising so much as a murmur; nay, that the very buildings themselves should have been pulled down without a protest.... It seems to us impossible that the tombs of so many worthies should have been destroyed without the indignation of all who knew the story of the past.... Yet ... it is unfortunately too true that there is not, at any time or with any people, reverence for things venerable, old, and historical, save with a few. The greater part are careless of the past, unable to see or feel anything but the present.... The parish churches were filled with ruins, ... the past was gone.... The people lived among the ruins but regarded them not, any more than the vigorous growth within the court of a roofless Norman castle regards the donjon and the walls. They did not inquire into the history of the ruins; they did not want to preserve them; they took away the stones and sold them for new buildings."

Yet, though in London's history there were, as we have seen, occasional great upheavals, such as the Reformation, the Fires, the Protectorate, it was more the rule of change that went on unceasingly between whiles—change, such as we see it to-day, the incessant beat of the waves on the shore—that (p. 9) has obliterated the former time. "The old order changeth, giving place to new"; and strange indeed it is, when one comes to think of it, that anything at all should be left to show what has been. The monasteries, the priories, the churches, that once occupied the greater portion of the city, and filled it with the clanging of their bells, so that the city was never quiet—these, of course, had mainly to go. The Church had to make way for Commerce; the Monasteries for the Merchants. The London of the early Tudors was still more or less that of Chaucer, and contained the same Friars, Pardoners, and Priests. The paramount importance of the Church is shown by the old nursery legends that circle round Bow bells; and the picturesque figure of Whittington, the future Lord Mayor, listening, in rags and dust, to the cheering church bells that tell him to "turn again," is really the connecting link between the Old and the New Age.

A few of the great monastic foundations of London escaped Henry VIII.'s acquisitive zeal, and have, as modern school-boys have reason to know, been devoted to educational and other charitable aims. It was, indeed, eminently suitable that in the classic precincts of the ruined monastery of the "Grey Friars" should arise a great school—the School of Christ's Hospital (colloquially termed the "Blue-Coat School")—where, till but the other day, the "young barbarians" might be seen at play behind their iron barriers, backed by the fine old whitely-gleaming, buttressed hall that faces Newgate Street. It was fitting, too, that the early dwelling of the English Carthusian monks—the place where Prior Houghton, with all the staunchness of his race, met death rather than cede to the tyrant one jot of his ancient right—should become not only a great educational foundation, but also a shelter for the aged and the poor. We know it as the "Charterhouse"; as a picturesque, rambling building of sobered red-brick, built around many courtyards, its principal entrance under an archway that faces the quiet Charterhouse Square. The place (p. 10) has a monastic atmosphere still; to those, at least, who reverently tread its closes and byways—byways hallowed yet more by inevitable association with the sacred shade of Thomas Newcome; shadow of a shade, indeed! fiction stronger, and more enduring, than reality!

Yet the Charterhouse is, so to speak, an "insula" by itself in London, a world of its own; possessing an ancient sanctity undisturbed by the neighbouring din of busy Smithfield, the unending bustle of the great city. More essentially of London is the curious unexpectedness of buildings, places, and associations. What is so strange to the inexperienced wanderer among London byways is the manner in which bits of ancient garden, fragments of old, forgotten churchyards, isolated towers of destroyed churches, deserted closes, courts and slums of wild dirt and no less wild picturesqueness, suddenly confront the pedestrian, recalling incongruous ideas, and historical associations puzzling in their very wealth of entangled detail. The "layers" left by succeeding eras are thinly divided; and the study of London's history is as difficult to the neophyte as that of the successive "layers" of the Roman Forum.

The Shoeblack.

It is sometimes refreshing to note that, even in the City and in our own utilitarian day, present beauty has not been altogether lost sight of. There is in modern London, as a French writer lately remarked, "no street without a church and a tree"; this is especially true of the City, where, even in crowded Cheapside, the big plane-tree of Wood Street still towers over its surrounding houses, hardly more than a stone's throw from the shadow cast by the white steeple of St. Mary-le-Bow, glimmering in ghostly grace above the busy street. So busy indeed is the street, that hardly a pedestrian stays to notice either church or tree; yet is there a more beautiful highway than this in all London? It is satisfactory to reflect—when one thinks of the accusation brought against us that we are "a nation of shopkeepers"—on what this one big (p. 11) plane-tree costs a year in mere lodging! Wandering northward from Cheapside down any of the crowded City lanes with their romantic names, through the mazes of drays and waggons—where porters shout over heavy bales, and pulleys hang from upper "shoots"—you may find, in a sudden turn, small oases (p. 12) of quiet green churchyard gardens—for some unexplained reason spared from the prevailing strenuosity of bricks and mortar—where wayfarers rest on comfortable seats, provided by metropolitan forethought, from daily toil. In these secluded haunts are many spots that will amply reward the sketcher. Specially charming in point of colour are the gardens of St. Giles, Cripplegate; these, though closed to the general public, are overlooked and traversed by quiet alleys, affording most welcome relief from the surrounding din of traffic. Here sunflowers and variegated creepers show out bravely in autumn against the blackened mass of the tall adjoining warehouses, whence a picturesque bastion of the old "London Wall" projects into the greenery, and the church of St. Giles, with its dignified square tower, dominates the whole. The author of The Hand of Ethelberta has, in that novel, paid graceful homage to the church and its surroundings. The little bit of vivid colour in the sunny churchyard (it is part rectory garden, and is divided by a public path since 1878), affords a standing rebuke to the unbelievers who say gaily that "nothing will grow" in London. A delightful byway, indeed, is this parish church of Cripplegate! Its near neighbourhood shows, by the way, hardly a trace of the disastrous fire it so lately experienced. From the corner of the picturesque "Aerated Bread Shop"—of all places—that abuts on to the church, a delightful view of all this may be had. This ancient lath-and-plaster building will, no doubt, in time be compelled to give way to some abnormally hideous new construction, but at the present day it is all that could be wished; and, though so close to the hum of the great city, so quiet withal, that the visitor may, for the nonce, almost imagine himself in some sleepy country village. And thus it is in many unvisited nooks in the busy City. "The world forgetting, by the world forgot," is truer of these byways than of many more rural places. For the eddies of a big river are always quieter than the main stream of a small canal. In the world, yet not of it, are, too, these (p. 13) strangely old-fashioned rectories, sandwiched in between tall, overhanging city warehouses.

But the sprinkling of old churches, with their odd, abbreviated churchyards, that are still to be found amid the busy life of the City of London, hardly does more than faintly recall that picturesque and poetic time when the church and the convent were pre-eminent. The great temporal power of the Church in London, that held sway during long centuries, is vanished, forgotten, supplanted as if it had never been. Do the very names of Blackfriars and Whitefriars suggest, for instance, to us, "the latest seed of time," anything more than the shrieking of railway terminuses, or the incessant din of printing machines? For, while the memory of the "Grey Friars" and that of the Carthusians is still honoured and kept green in the dignified "foundations" of Christ's Hospital and of the Charterhouse,—the orders of the "White" and "Black" Friars, of the Carmelites, and the stern Dominicans, have descended to baser and more worldly uses. Destroyed at the Reformation, its riches alienated, its glory departed, the splendid Abbey Church of the Dominicans came to be used as a storehouse for the "properties" of pageants; "strange fate," says Sir Walter Besant, "for the house of the Dominicans, those austere 'upholders of doctrine.'" For the dwelling of the "Carmelites," or "White Friars," an Order of "Mendicants" these,—another destiny waited—a destiny for long lying unfolded in the bosom of our "wondrous mother-age." Mysterious irony of Fate! that where the Carmelite monks, in their Norman apse, prayed and laboured; where the Mendicant Friars wandered to and fro in the echoing cloister, the thunder of the printing-press should have made its home:

"There rolls the deep where grew the tree,

O earth, what changes hast thou seen!

There, where the long street roars, hath been

The stillness——"

—The "Daily Mail Young Man"—that smart product of a (p. 14) later age—has now his home in Carmelite Street; the "Whitefriars' Club" is a press club; the gigantic machines that print the world's news shake the foundations of St. Bride's; and the shabby hangers-on of Fleet Street—though of a truth, poor fellows, often near allied to mendicants—are yet, it is to be feared, only involuntarily of an ascetic turn. The contrast—or likeness—has served to awaken one of Carlyle's most thunderous passages: "A Preaching Friar,"—(he says),—"builds a pulpit, which he calls a newspaper:

"Look well" (he continues),—"thou seest everywhere a new Clergy of the Mendicant Orders, some bare-footed, some almost bare-backed, fashion itself into shape, and teach and preach, zealously enough, for copper alms and the love of God."

Carlyle, apparently, nursed an old grudge against the press,—for this is not the only occasion when he fulminates against the new order of Mendicants. The theatres, also, that succeeded the monasteries of Blackfriars were, here too, supplanted by the Press; under Printing-House-Square only lately, an extension of the Times Office brought to light substantial remains.

But the Church was not the only mediæval beautifier of London; as her temporal power and splendour waned,—the splendour of the merchants grew and flourished. For the great supplanter of the power of the Church was, as already hinted, the power of the City Companies. These immense trades-unions began to rise in the fourteenth century, when the old feudal system gave way to the civic community;—and they increased greatly in strength after the dissolution of the Monasteries. These companies incorporated each trade, and had supreme powers over wages, hours of labour, output, &c. In the beginning they were, like everything else, partly religious, each company or "guild" having its patron saint and its special place of worship;—the Merchant Taylors, for instance, being called the "Guild of St. John";—the Grocers, the "Guild of St. Anthony"; while St. Martin protected the saddlers, and so on. These guilds in time receiving Royal charters, became very rich (p. 15) and powerful, till the year 1363 there were already thirty-two companies whose laws and regulations had been approved by the king. If any transgressed these laws, they were brought before the Mayor and Aldermen. We have still the Mayor and Aldermen, but the city companies (whose principal function was the apprenticing of youths to trades), have merely the shadow of their former authority, and their business is now mainly charitable, ceremonial, and culinary. Yet though their powers are diminished, their splendid "halls" are still among the most interesting "sights" of the City. Visits to these massive and solid palaces, some of them of great splendour, and rising like pearls among their often (it must be confessed) unsavoury surroundings, give a good idea of the immense wealth of those mediæval merchant princes, and help the stranger to realize the strength of that power that was able to resist the attempts of kings to break its charter. Such sturdy independence, such insistence on her civic rights, has always been a main element of London's greatness.

When the Strand is up.

I have only touched at the mere abstract of London's voluminous history,—only enumerated a poor few of her Highways and Byways; the subject, in truth, is too great to exhaust even in a whole library of books. It is, indeed, the principal drawback to the study of London that she is too vast—that the student is ever in danger of "not seeing the forest for the trees." Her byways are as the sands of the sea in multitude; her history is the history of the world. It is, perhaps, better that the stranger to the metropolis should take in hand a small portion at a time,—and try to grasp that thoroughly,—than lose himself in an intricate maze of buildings and associations. To read the history of London aright,—to see and feel in London stones all that can be seen and felt, requires not only untiring energy, but also knowledge, sympathy, intuition, patriotism, one and all combined. To know London really well, one should gain an intimate acquaintance with her from day to day, not being contented with the (p. 16) common and well-known ways, but ever penetrating into fresh haunts. From all the great highways of London, from the Strand, Fleet Street, Piccadilly, Holborn, Oxford Street, convenient excursions may be made into the surrounding neighbourhood; which often, in different parts of London, is, so far as inhabitants, appearance, manners and customs go, really (p. 17) a complete and distinct city by itself. Does not "Little Britain" differ widely from its neighbouring Clerkenwell? Soho as widely from its adjacent Bloomsbury? and the immaculate Mayfair from the more doubtful Bayswater? Who does not recall what Disraeli—that born aristocrat in his tastes—said of the people who frequent the plebeian, though charming, Regent's Park?

"The Duke of St. James's," (he says),—"took his way to the Regent's Park, a wild sequestered spot, whither he invariably repaired when he did not wish to be noticed; for the inhabitants of this pretty suburb are a distinct race, and although their eyes are not unobserving, from their inability to speak the language of London they are unable to communicate their observations."

So far from being merely one town, London is really a hundred townlets amalgamated. The visitor can there find everything that he wants; he must, however, know exactly what it is that he wants to find. Does he desire to see pictures? many galleries of priceless works of art are within a stone's throw, free, ready, waiting only to be seen; does he prefer realism and life? the "street markets" of Leather Lane and of Goodge Street are instinct with all possible types of humanity; does he yearn for peaceful solitude, historic association? the quiet nooks of the Temple invite him; is it solitary study that his soul craves? the immense library of the British Museum offers him all its treasures; does he merely wish to perambulate vaguely? even the prosaic Oxford Street presents a very kaleidoscope of human life. Nevertheless, in his perambulations, the wanderer should receive a word of warning: let him beware of asking for local information (save indeed, it be of a policeman), for two reasons. Firstly, because no born Londoner of the great middle class ever knows, except by the merest accident, anything whatever about his near neighbourhood; and, secondly, because if he do get an answer, he is morally certain to be misdirected. The wanderer should always start on his expeditions with a distinct (p. 18) plan in his own mind of the special itinerary he wishes to adopt,—be that itinerary Mr. Hare's, or any other man's,—and he should never allow himself to be drawn off from it to another tangent. Even this crowded highway of Oxford Street, "stony-hearted stepmother," old gallows-road, passing from Newgate Street to Tyburn Tree, and bearing so many different names in its course,—beginning, as "Holborn," in City stress and turmoil, intersecting the very centre of fashion at the Marble Arch, and continuing as the "Uxbridge Road," to High Street, Notting Hill,—passes through all sorts and conditions of men and things. Tottenham Court Road, that glaring, fatiguing thoroughfare, which through all its phases ever "remains sordid, sunlight serving to reveal no fresh beauties in it, nor gaslight to glorify it," begins in comparative honour in New Oxford Street, to descend through bustle and racket to the noisy taverns and purlieus of the Euston Road. That sylvan village and manor of "Toten Court," where city folk repaired in old days for "cakes and creame," seems far enough away now! Fenchurch Street,—or rather its continuation Aldgate Street,—as it merges into the long "Whitechapel Road," becomes more and more dreary; not even its soft-gliding, cushioned tram-cars lending enchantment to the depressing scene. Waterloo Road and Blackfriars Road, "over the water," as they trend southwards pass through strange and often unsavoury purlieus. Every district has its special idiosyncrasies. Piccadilly and St. James's are always aristocratic. Pall Mall has a severe and solid dignity; while the Strand and its continuation, the narrow and tortuous Fleet Street, are instinct with ancient honour and literary association. Yet, even here, if the visitor have not the "seeing eye" that discerns the past through the present, he may "walk from Dan to Beersheba and find all barren."

The great charm, however, of London lies in its unsuspected courts and byways. From most of these big thoroughfares you may be transported, with hardly more than a step, into (p. 19) picturesque nooks of sudden and almost startling silence, or, rather, cessation from din. All who know and love London will recall this. From busy Holborn to the aloofness of quiet Staple Inn, with its still, collegiate air, what a change from the turmoil of Fleet Street to the closes of little Clifford Inn, with its old-world, forgotten air. From High Street, Kensington, too, that town with all the air of a smart suburb, how many charming excursions may not be made on Campden Hill and in Holland Park—a neighbourhood full of artistic and literary charm. In Westminster, what quiet, secluded nooks, and green closes, abound for the sketcher, and how lovely are the gardens of the Green Park and St. James's Park, bordered by the stately palaces of St. James's, and the picturesque houses of Queen Anne's Gate. And all along the river embankment, from Westminster to the Tower, are interesting streets and nooks full of historic and literary association. The embankment, running, at first, parallel with the noisy Strand; reaching classic ground in the quiet Temple, by that garden where the "red and white rose" first started their bloody rivalry, becomes then muddy and uncared for before the newspaper land of Whitefriars; beyond, again, are blackened wharves, which gradually degenerate into the terrible and utterly indescribable fishiness of Billingsgate, and unpoetic Thames Street! Then, the "Surrey side" of the river,—Southwark and Chaucer's Inns, or what yet remains of them,—would form several delightful excursions; to say nothing of the Tower, with its innumerable historic associations,—and, perhaps, a visit to Greenwich in summer time. The old churches of the City would, as I have hinted, take many days to explore thoroughly; the Holborn and Strand Inns of Court and of Chancery, especially the Temple and Staple Inn, should be known and studied well; nothing can exceed the charm of these quiet and secluded "haunts of ancient peace."

Space, however, is limited; I have now said enough to give some idea, even to the uninitiated, of London's many (p. 20) highways and byways, with their suggestions and associations. Yet one word of caution I would add: London must be approached with reverence; her cult is a growth of years, rather than a sudden acquisition. And the love of London stones, once acquired, never leaves the devotee. Whether he walk blissfully through Fleet Street with Johnson and Goldsmith, linger by the Temple fountain with Charles Lamb or Dickens, or traverse the glades of Kensington Gardens with Addison and Steele, "where'er he tread is haunted, holy ground." Here, on Tower Hill, once stood spikes supporting ghastly heads of so-called "traitors"; there, at Smithfield, were burned numberless martyrs. Even the London mud has its poetic associations. We may all tread the same road as that once trodden by Rossetti and Keats; strange road:

"Miring his outward steps who inly trode

The bright Castalian brink and Latmos' steep."

Yes, the love of London grows on the constant Londoner. He will not be long happy away from the comforting hum of the busy streets, from the mighty pulse of the machine. In absence his heart will ever fondly turn to "streaming London's central roar," to the spot where, more than anywhere else, he may be at once the inheritor of all the ages.

How interesting would it be if one could only—by the aid of some Mr. Wells's "Time Machine"—take a series of flying leaps backward into the abysm of time! Strange to imagine the experience! Beauty, one reflects, might be gained at nearly every step, at the expense, alas! of sanitary conditions, knowledge, and utility. Let us, for a moment, imagine how the thing would be.... First, in a few rapid revolutions of the wheel, would disappear the hideous criss-cross of electric wires overhead, the ugly tangle of suburban tram-lines, and the greater part of the hideous modern growth of suburbs.... Another whirl of the machine, and every sign of a railway station would disappear, every repulsive engine shed and siding (p. 21) vanish ... while the dull present-day rumble of the metropolis would give place to a more indescribably acute and agonising medley of sound.... Again a little while, and the hideous early Victorian buildings would disappear, making way for white Stuart façades, or sober red-brick Dutch palaces.... With yet a few more revolutions, the metropolis will shrink into inconceivably small dimensions, and the atmosphere of the city, losing its peculiar blue-grey mist, will gradually brighten and clear—a radiance, unknown to us children of a later day—diffusing itself over the glistening towers and domes, no longer blackened, but gleaming, Venetian-like, in the Tudor sunlight.... The aspect of the river too has changed; no more ugly steamers, but an array of princely barges deck its waters, gay with the bright dresses of ladies and gallants.... Its solid embankments have crumbled to picturesque overgrown mud banks, its many bridges shrunk to one; the little separate towns of "London" and "Westminster" presenting now more the appearance of rambling villages, adorned by some palaces and churches.... Another turn of the machine, and lo! the imposing façades that adorned the Strand have in their turn given way to picturesque rows and streets of overhanging gabled houses with blackened cross-beams, their quaint projecting windows almost meeting over the narrow streets ... stony streets with their crowds of noisy, jostling, foot-passengers.... Again a long pause ... and now the scene changes to Roman London, the ancient "Augusta," with its powerful walls, its slave ships and pinnaces, its mailed warriors, ever in arms against the blue-eyed Saxon marauders. Then—a final interval—and we see the primitive British village, its mud huts erected by the kindly shores of our "Father Thames," their smoke peacefully rising heavenwards above the surrounding marshes and forests.

(p. 22)

Waterloo Bridge.

"Above the river in which the miserable perish and on which the fortunate grow rich, runs the other tide whose flood leads onto fortune, whose sources are in the sea empire, and which debouches in the lands of the little island; above the river of the painters and poets, winding through the downs and meadows of the rarest of cultivated landscape out to the reaches where the melancholy sea breeds its fogs and damp east winds, is that of the merchant and politician, having its springs in the uttermost parts of the earth, and pouring out its golden tribute on the lands whence the other steals its drift and ooze."—W. J. Stillman.

"Above all rivers, thy river hath renowne....

O! towne of townes, patrone and not compare,

London, thou art the Flour of Cities all."—Dunbar.

No one, be he very Londoner indeed, has ever seen the great city aright, or in the true spirit, if he have not made the (p. 23) journey by river at least as far as from Chelsea to the Tower Bridge. From even such a commonplace standpoint as the essentially prosaic Charing Cross Railway Bridge some idea can be gained of the misty glory of this highway of the Nations. It is indeed, often one of these condemned approaches to London that give the traveller the best idea of the vast and multitudinous city. London railway approaches are often abused, even anathematized, yet surely nowhere is the curious picturesqueness of railways so proved as by the impressive approach to Charing Cross Station, across the mighty river. Here, at nightfall, all combines to aid the general effect; the mysterious darkness, the twinkling lights of the Embankment, reflected in the dancing waters, and cleansed by the white moonlight. What approach such as this can Paris offer? But, if the traveller be wise, he will soon seek to supplement such initiatory views by pilgrimages on his own account, pilgrimages undertaken in all reverence, up and down the stream. For, whatever Mr. Gladstone may have said of the omnibus as a mode of seeing London, may be reiterated more forcibly as regards the deck of a penny steamer. It is the fashion to call London ugly; Cobbett nicknamed it "the great wen"; Grant Allen has called it "a squalid village"; and Mme. de Staël "a province in brick." Yet, how full of dignity and beauty is the city through which this wide, turbid river rolls!—"the slow Thames," says a French writer, "always grey as a remembered reflection of wintry skies." Here, by day, hangs that veiling blue mist, which is the combined product of London fog and soot, adding all the indescribable charm of mystery to the scene; and, as twilight draws on, the grand old buildings loom up, vaguely dark, against the sky, their added blackness of soot giving a suggestion as of solidity and antiquity; that poetic time of twilight, "when," as Mr. Whistler puts it.

"The evening mist clothes the riverside with poetry, as with a veil, and the poor buildings lose themselves in the dim sky, and the tall chimneys (p. 24) become campanili, and the warehouses are palaces in the night, and the whole city hangs in the heavens, and fairyland is before us."

At night, the scene changes: the vast Embankment shines with lamps all a-glitter, and behind them the myriad and deceitful "lights of London" twinkle like a magician's enchanted palace.

And it is altogether in the fitness of things that the river should be both introduction and entrance gate, so to speak, of modern London. For it is the river, it is our "Father Thames," indeed, that has made London what it is. In our childhood we used to learn in dull geography books, as inseparable addition to the name of any city, that it was "situated" on such-and-such a river; facts that we then saw little interest in committing to memory, but, nevertheless vastly important; how important, we see from this city of London. For London is, and was, primarily a seaport. In Sir Walter Besant's interesting pages may be read the story of the early settlers—Briton, Roman, Saxon, Norman—who successively founded their infant settlements on this marshy site, and had here their primitive wharves, quays, and trading ships for hides, cattle, and merchandise. It is the river, more than anything else, that recalls the past history of London. For London, ever increasing, ever rebuilt, has buried most of her eventful past in an oblivion far deeper than that of Herculaneum. Nothing destroys antiquity like energy; nothing blots out the old like the new. London, ever rising, like the phœnix, from her own ashes, has by the intense vitality of her "to-days" always obliterated her "yesterdays." It is only in dead or sleeping towns that the ashes of the past can be preserved in their integrity, and London has ever been intensely alive. Yet, gazing on the silvery flow of the river, we can imagine the Roman embankment, the hanging gardens, that once stretched from St. Paul's to the Tower; the Roman city, with its forums and basilicas, that once crowned prosaic Ludgate Hill—Roman pinnace, Briton coracle, Saxon ship, Tudor vessel—we can see them all in their (p. 25) turn—crowned by the spectacle of Queen Elizabeth in her gaily-hung state barge, with her royal procession; or, in more mournful key, her body, on its death-canopy—a barge "black as a funeral scarf from stern to stem," on that sad occasion when

"The Queen did come by water to Whitehall.

The oars at every stroke did teares let fall."

If in the crowded day of London—with the shouting of bargees, the whistle of steam-tugs, and the puffing of the smoke-belching trains overhead, indulgence in such dreams is well-nigh impossible,—in the mysterious night, when the slow misty moon of London climbs, it is easy, even from an alcove of Waterloo Bridge, to indulge the fancies of

"That inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude."

The so-called "penny steamers" of London, which run, during the summer months, at very cheap rates between London Bridge and Chelsea, form the best way of seeing and appreciating the vast city. For those who do not mind rather close contact with "the masses"—braying accordions, jostling fish-porters, sticky little boys, and other inseparable adjuncts of a crowd whose "coats are corduroy and hands are shrimpy"—this mode of becoming acquainted with London will be found very satisfactory. The ways of the said steamers are often, it is true, somewhat erratic; yet if, on a warm June day, the stranger go down to the river in faith, his expectancy will generally be rewarded. Up comes the puffing, creaky little tug, making the tiny landing stage vibrate with the sudden shock of contact; there is an immediate rush to embark, and, on a fine day, you are, at first, happy if you get standing-room. Cruikshank's pictures, Dickens's sketches—how suggestive of these is the motley crowd of faces that line the boat,—faces on which the eternal "struggle for life" has printed lines, as it may be, of carking care, of blatant self-satisfaction, of crime and degradation. (p. 26) To quote William Blake, the poet-painter,—a Londoner, too, of the Londoners:

"I wander through each chartered street

Near where the chartered Thames does flow,

A mark in every face I meet,

Marks of weakness, marks of woe."

The fine, broad Chelsea reach of the river, looking up towards Fulham from the Albert chain-bridge, is wonderfully picturesque. Here, especially on autumn nights, may be seen in all their splendour the brilliant sunsets that Turner loved to paint, and that, propped up on his pillow, he turned his dying eyes to see. The ancient and unassuming little riverside house where Turner spent his last days is still standing; but its tenure is uncertain, and it may soon vanish. It stands (as No. 119)—towards the western end of Cheyne Walk—the walk that begins in the east so magnificently, and decreases, as regards its mansions, in size and splendour as it approaches the old historic red-brick church of Chelsea. Yet, small as Turner's riverside abode is, it is more celebrated than any of its neighbours, for it was here that the greatest landscape painter of our time lived. Here, along the shores of the river, flooded at eve "with waves of dusky gold," the shabby old man with such wonderful gifts used to wander in search of the skies and effects he loved; here he was hailed by cheeky street arabs, as "Puggy Booth" (the legend of the neighbourhood being that he was a certain retired and broken-down old "Admiral Booth"). Here he sat on the railed-in house-roof to see the sun rise over the river, and here, when too weak to move, his landlady used to wheel his chair towards the window that he might see the skies he so loved. "The Sun is God," were almost his last words. Thus, he who as a boy of Maiden Lane had spent his early years on the river near London Bridge—by the Pool of London, with its wharves and shipping—died, faithful to his early loves, in a small Chelsea riverside cottage. The row of irregular riverside (p. 27) houses, of which Turner's cottage is one, becomes more palatial lower down, across Oakley Street. In summer, what more lovely than the view from these houses, over the shining Chelsea reach, towards the feathery greenness of distant Battersea Park? a view which, even beyond the park limits, not even the too-conspicuous sky-signs or factory chimneys on the further shore can altogether abolish or destroy. So many things in London, ugly in themselves, are lent "a glory by their being far"; and even Messrs. Doulton's factory chimneys, seen through the blue-grey river mist, have, like St. Pancras Station, often the air of some gigantic fortress. This same blue-grey mist of London, especially near the river, is rarely ever entirely absent. Chemists may tell you that it is merely carbon, a product of the soot, but what does that matter? In its own place and way it is beautiful. The heresy has before now been ventured, that London would not be half so picturesque if it were cleaner; and from the river this fact is driven home more than ever to the lover of the beautiful. Blackened wharves, that through the dimmed light take on all the air of "magic casements,"—great bridges, invisible till close at hand, that loom down suddenly on the passing steamer with the roar of many feet, a rattle of many wheels, a rumble of many trains; vast Charing-Cross vaguely seen overhead—immense, grandiose, darkening all the stream; the Venetian-white tower of St. Magnus, gleaming all at once before blackened St. Paul's; and, most popular of all London views, the tall Clock Tower of the Houses of Parliament, with its long terraced wall, reflecting its shining lines in the broad waters. As ivy and creepers adorn a building, so does the respectable grime of ages clothe London stones as with a garment of beauty.

The "respectable grime of ages" can hardly however be said yet to cover the newest Picture Gallery of London, glimmering ghostlike by the waterside, Sir Henry Tate's magnificent and splendidly housed gift, which rises whitely, like some Greek Temple of Victory, amid the dirty, dingy (p. 28) wharves, and generally slummy surroundings of the debatable ground that divides the river-frontages of Pimlico and Westminster. The changes of Time are curious. Here, where once stood Millbank Penitentiary, now rises a stately Palace adorned by pillars, porticoes and statues; wherein are enshrined some of the nation's most precious treasures, all the master-pieces of the modern school of English Art. Sir Henry Tate, a "merchant prince" of whom the country may well be proud, was a large sugar refiner, and we owe this imposing building, with a large part of its contents, to those uninspiring wooden boxes, so familiar to us for so many years back, labelled "Tate's Cube Sugar."

The interior of the Tate Gallery (its proper denomination is, I believe, "the National Gallery of British Art,") is very delightfully planned. A pretty fountain fills the central hall of the gallery under the dome; an adornment as refreshing as it is unexpected. For London, the home of riches, is strangely niggardly with her fountains. Yet Rome, the city of fountains, had to bring all her water for many miles, and over endless aqueducts! The immediate riverside surroundings of the Tate Gallery are, as described, hardly grandiose; yet the timber-wharves and stone-cutters' sheds that here share the muddy banks with the ubiquitous tribe of London "Mudlarks," are not without their picturesque "bits." Old boats sometimes reach here their final uses; and even portions of old derelicts, like the "Téméraire," often find their way here at last. Witness advertisements like the following:

Fires.—Logs of old oak and ship timber, from Old Navy ships broken up, in suitable sizes, for sitting-room use, so famous for beautifully coloured flames, can only be obtained from the ship breaking yard of —— Baltic Wharf, Millbank, S.W.

It is, however, only the wharves and the mudlarks that are visible from the river itself; for the quaint gates of these timber-yards, opening on to the Grosvenor Road, and surmounted (p. 29) by their "signs" in the shape of ghostly white figure-heads—the figure-heads of real ships—are only visible to those who make their way along this mysterious region by land. These colossal creatures, indeed, projecting often far into the road, pull up the pedestrian with such alarming and human suddenness that it would surely require, in the uninitiated, a strong mind and a good conscience to travel this way alone on a dark night.

The keynote of London is ever its close juxtaposition of splendour and misery, "velvet and rags." Therefore, after skirting the shore of Millbank, it strikes the Londoner as quite natural, and in the usual order of things, that he should suddenly and without any preface find his vessel gliding, in an abrupt hush, underneath the terrace-wall of the most well-known and most be-photographed edifice in London; under the high vertical wall, with its softly lapping waters, that guards the terrace of the Houses of Parliament. Classic retreat, where none but the specially bidden may enter! The great towers, with the vast building they surmount, darken, for a moment, all the stream by the intense shadow they cast, to mirror themselves anew in charming proportion as we descend the stream and they recede.

Exactly opposite the Houses of Parliament are those curious seven-times-repeated red-brick projections of St. Thomas's Hospital, which are so prominent an object from the Terrace, that a fair American visitor, while taking her tea there, is said to have once innocently inquired: "Are those the mansions of your aristocracy?" Mr. Hare unkindly suggests that their chief ornament, a "row of hideous urns upon the parapet, seems waiting for the ashes of the patients inside."

A little higher, on the Surrey side, is the historic Lambeth Palace, for nearly seven hundred years the residence of the Archbishops of Canterbury:

"Lambeth, envy of each band and gown,"

(p. 30) says Pope truly. But the gifts of Fortune are, alas! seldom ungrudging; and, sad thought! by the time the poor Archbishops have reached the zenith of fame and comfort in their Lambeth paradise, their multifarious duties must effectually prevent their ever having time thoroughly to enjoy their "garden of peace." It is a lovely home, and commands perfect views. Quite Venetian-like, when night's canopy has fallen, do the lights of Westminster Palace appear from the Lambeth shore; the lighted Tower, which proclaims to all the world the fact that Parliament is sitting, reflected like a solitary full moon in the dark transparency of the waters. Lambeth Palace is, indeed, a charming spot, both for its views up and down the river and for its associations. In all its squareness of darkened red brick, it is very picturesque; the gateway with its Tudor arch, the chapel, and the so-called "Lollards' Tower," are, besides being historically interesting, fine subjects for an artist. At the gateway an ancient custom is observed:

"At this gate the dole immemorially given to the poor by the Archbishops of Canterbury is constantly distributed. It consists of fifteen quartern loaves, nine stone of beef, and five shillings' worth of half-pence, divided into three equal portions, and distributed every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday, among thirty poor parishioners of Lambeth; the beef being made into broth and served in pitchers."

In the Lollards' Tower are some curious relics of the barbarous tortures of the Middle Ages; and in the guard-room, or dining hall of the Palace, is a series of portraits of all the Archbishops from Cranmer to Benson. The modern and residential portion of the Palace, in the Tudor style, is contained in the inner court; it was rebuilt by Archbishop Howley in 1820. Howley was the last Archbishop who lived here in state and kept open house; "the grand hospitalities of Lambeth have perished," as Douglas Jerrold said, "but its charities live." The ancient portions of the palace have known many vicissitudes of fortune; Cranmer adorned his house, and loved to beautify his garden; Wat Tyler and his rebels plundered the (p. 31) palace and beheaded Sudbury, its then archbishop: and Laud, who had a hobby for stained glass, filled the chapel windows with beautiful specimens, which were all subsequently smashed by the Puritans. The palace, after having been used successively as a prison, a place of revel, and a garrison stronghold, now enjoys all the serenity of old age and quiet fortunes; its solid red brick, which time darkens so prettily, looking ever across the waters in calm dignity towards the taller stones of Westminster,—the spiritual contrasted with the temporal.

The tower of the ancient church of St. Mary, Lambeth, close by the Palace, is memorable as the shelter of Queen Mary of Modena, James II.'s unfortunate wife, on the dramatic occasion of her flight from Whitehall with her infant son (the "Old" Pretender), on a wild December night of 1688:

"The party stole down the back stairs (of Whitehall), and embarked in an open skiff. It was a miserable voyage. The night was bleak; the rain fell; the wind roared; the water was rough; at length the boat reached Lambeth; and the fugitives landed near an inn, where a coach and horses were in waiting. Some time elapsed before the horses could be harnessed. Mary, afraid that her face might be known, would not enter the house. She remained with her child, cowering for shelter from the storm under the tower of Lambeth Church, and distracted by terror whenever the ostler approached her with his lantern. Two of her women attended her, one who gave suck to the Prince, and one whose office was to rock the cradle; but they could be of little use to their mistress; for both were foreigners who could hardly speak the English language, and who shuddered at the rigour of the English climate. The only consolatory circumstance was that the little boy was well, and uttered not a single cry. At length the coach was ready. The fugitives reached Gravesend safely, and embarked in the yacht which waited for them."—Macaulay.

St. Mary's is the mother church of the manor and parish, and its tower dates from 1377:

"In this church is a curious 'Pedlar's Window,' with a romantic story attached to it. When the church was founded, it is said that a pedlar left an acre of land to the parish, on condition that a picture of himself, his pack and his dog, should be preserved in the church. This was accordingly done; the pedlar was commemorated in the glass of the window, and the (p. 32) value of the acre, at first 2s. 8d., increased till in our day it is worth £1000 a year. In 1884, some local iconoclasts actually removed the pedlar from the window, to put up modern glass to the relatives of certain officials. Popular indignation, however, has since reinstated the injured pedlar, with his pack and dog, in their place."

But Lambeth, however charming and historic, is still "the Surrey Side", and the glories of the Albert Embankment pale before those of the Victoria Embankment, one of the greatest London improvements of the century. Of course it has its critics,—of the order who cavil at the poor Romans for embanking their devastating yellow Tiber. But it is the fashion for us to abuse our London monuments, and to deride them as the work of a "nation of shopkeepers." The Londoner rarely approves of anything new or even modern. Of the Chelsea Embankment, all that Mr. Hare says is that "it has robbed us of the water stairs to the Botanic Garden, given by Sir Hans Sloane." Does not even Mr. Ruskin fall foul of the innumerable straight lines of the Palace of Westminster, and of its stately Clock Tower, as testifying to the sad want of imagination shown by the modern English architect? (But Mr. Ruskin must surely that day have been in search for a windmill to tilt against, for the abused "straight lines" do not prevent this being one of the loveliest of London views.) And does not M. Taine pour the vials of his wrath on to the great river Palace of Somerset House, with its "blackened porticoes filled with soot"? "Poor Greek architecture," he adds compassionately, "what is it doing in such a climate?" Evidently the idea of the artistic value of soot, to which I have already alluded, had not occurred to him.

The noble Victoria Embankment now runs where of old, in Elizabethan times, ran a glittering, almost Venetian, river-frontage of palaces. And where the old palaces stood in Tudor days, stand now enormous hotels—the palaces of our own day—each newer hotel in its turn eclipsing the other in size, magnificence, expense. The picturesque "Savoy," with its (p. 33) river balconies, the stately "Cecil," with its wonderful banqueting halls, and, further from the river, the spacious "Métropole," the "Grand," the "Victoria." All these hotels are so recent as to impress one fact upon us—the fact that London has really only lately become a tourist haunt. Statistics, indeed, show now that London attracts more visitors than any other great European town. Twenty-five years ago, it was as hard to find a good, clean, and thoroughly satisfactory London hotel, as it was to get a cup of tea for less than sixpence; or, indeed, a good one at all! But times have changed. Big hotels now, like flats, threaten to be overdone. We can well imagine the disappointment of the foreign visitor to London on discovering the names and uses of the fine buildings that adorn the river front between Westminster and Blackfriars. "What," he or she may ask, "is that imposing structure with Nuremberg-like green roofs, towering over the trees of the Embankment Gardens?" "That, Sir or Madam," answers politely the lady guide (for it is of course a charming and very certificated lady guide who "personally conducts" the party), "is Whitehall Court, a building let out in high class flats." "And what," continues the crushed tourist, "is that turreted, buttressed, red-brick edifice? Probably some rich nobleman's whim?" "Those, Madam, are the new buildings of Scotland Yard, recently designed by Mr. Norman Shaw, one of the most famous of our modern architects." "And what are those Venetian-like balconies, all hung with greenery and flowers?" "They belong, Madam, to the Savoy and Cecil Hotels. At the Savoy you may get a very nice dinner for a guinea; they have a wonderful chef; and in the enormous dining-hall of the Cecil, most of the great public banquets are given." "Truly, a nation of shopkeepers," the foreign visitor will re-echo sadly, as she dismisses her "lady guide."

Sightseers.

There is, I maintain, no finer walk in the world than that along the Victoria Embankment, from Blackfriars to Westminster. You may walk it every day of the year, and every (p. 35) day see some new, strange and beautiful effect of light, of water, of cloud. In midsummer, when the long row of plane trees offer a welcome shade and relief of greenery, and it is pleasant to watch the slow barges pass and repass; in autumn, when red and saffron sunsets flood all the west with light; in midwinter, when, sometimes, great blocks of ice line the turbid stream. One winter, not long past, when the Thames was all but frozen over, it was a curious and interesting sight to watch the crowd of sea-gulls, driven inshore by the intense cold, making their temporary home on the ice, and fed all day with raw meat and bread by thousands of sympathizing Londoners. Some of the birds had almost become tame when their compulsory visit came to an end.

The river, in old pre-embankment days, flowed at the foot of the curious ancient stone archway called "York Stairs," that stranded water-gate of old York House, which stands, lonely and neglected, in a corner of the Embankment Gardens. It has, however, survived, and that, in London, is always something. Its long buried, and now excavated, columns show the ancient level of the river, and the height to which the present Embankment has been raised. The Palace of York House, to which it was the river-gate, has gone the way of all palaces; its ruins (as all ruins must ever be in London), are thickly built over. Indeed, Somerset House is almost the only palace left to tell of the ancient river-side glories, glories of which Herrick wrote:

"I send, I send, here my supremest kiss

To thee, my silver-footed Tamasis,

No more shall I re-iterate thy strand

Whereon so many goodly structures stand."

Even Somerset House is merely an old palace rebuilt, for the present edifice is not much more than a century old. Buildings in London tend to become utilitarian; and Royalty, besides, has deserted the City for the West End. So the ancient Palace of the Lord Protector Somerset, that Palace (p. 36) that he destroyed so much to build, spent such vast sums on, and yet never lived in, but had his head cut off instead; the Palace that used to be the residence of the wives of the Stuart Kings, as described by Pepys, is now superseded by the vast Inland Revenue Office, with its myriad suites, corridors, chambers. Truly, a change typical of our busy and practical era!

Somerset House occupies the site of the older palace, a site almost equal in area to Russell Square. But the older palace, as befitted the "Dower House" of the Queens of England had gardens that extended along the river-shore. It was in Old Somerset House that Charles II.'s poor neglected Queen, Catherine of Braganza, used to sit all night playing at "ombre," a game which she had herself imported from Portugal; and it was here, in 1685, that three of her household were charged with decoying Sir Edmondsbury Godfrey into the precincts of the palace, and there strangling him. The wide courtyard of the interior has a bronze allegorical group by Bacon, of George III. mixed up with "Father Thames." Queen Charlotte, apparently rather resenting the ugliness of the representation, said to the sculptor, "Why did you make so frightful a figure?" The artist was ready with his reply. "Art," he said, bowing, "cannot always effect what is ever within the reach of Nature—the union of beauty and majesty." I myself must confess to some sympathy with Queen Charlotte; but the art of her day had ever a tendency to efflorescent excrescence.

On the river's very brink, a little higher up than Somerset House and its adjacent hotels, Cleopatra's Needle, that "great rose-marble monolith," stands guarded by two bronze sphinxes on a pediment of steps, backed by the Embankment and the trees of its gardens. The monolith is here in strange and novel surroundings. What ruins of empires and dynasties has not this ancient Egyptian obelisk seen! (p. 37) We poor human beings soon live out our little day, and are gone:

"The Eternal Saki from the Bowl hath poured

Millions of bubbles like us, and will pour——"

while this senseless block of stone lives for ever, regardless of the tides of humanity that ebb and flow ceaselessly about its feet. Has it not been a "silent witness" of the pageants of the magnificent Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty? Its hieroglyphics record its erection by Thotmes III., before the Temple of the Sun in On (Heliopolis), where it remained for the first 1600 years of its existence, and (says Mr. Hare) witnessed the slavery and imprisonment of the patriarch Joseph. The obelisk has had a strange and eventful history. Removed to Alexandria shortly before the Christian era, it was never erected there, but lay for years prone in the sand. Then, in 1820, Mahomet Ali presented it to the British nation; with, however, no immediate result. For, the difficulties of removal being great, no advantage was taken of the offer, till, in 1877, Mr. (afterwards Sir) Erasmus Wilson gave the necessary funds, amounting to £10,000. A special cylinder boat was made for the obelisk, but even with its removal its adventures were not ended, for, in the Bay of Biscay, the vessel encountered a terrific storm, and the crew of the ship that towed it, in peril of their lives, cut it adrift. For days it was lost, till a passing steamer happened to sight the strange-looking object and picked it up, earning salvage on it.

The granite is said to be slowly disintegrating and the hieroglyphics therefore becoming less deeply scored, by the action of the London smoke and mist—the mist glorified poetically by Mr. Andrew Lang in his "Ballade of Cleopatra's Needle";

"Ye giant shades of Ra and Tum,

Ye ghosts of gods Egyptian,

If murmurs of our planet come

To exiles in the precincts wan

(p. 38) Where, fetish or Olympian,

To help or harm no more ye list,

Look down, if look ye may, and scan

This monument in London mist!

"Behold, the hieroglyphs are dumb,

That once were read of him that ran

When seistron, cymbal, trump, and drum,

Wild music of the Bull began;

When through the chanting priestly clan

Walk'd Ramses, and the high sun kiss'd

This stone, with blessing scored and ban—

This monument in London mist.

"The stone endures though gods be numb;

Though human effort, plot, and plan

Be sifted, drifted, like the sum

Of sands in wastes Arabian.

What king may deem him more than man,

What priest says Faith can Time resist

While this endures to mark their span—

This monument in London mist?"—

It has been objected that Cleopatra's needle ought to have been placed somewhere else; for instance, in the centre of the Tilt Yard, opposite the Horse Guards. But it is, as I said, typical of Londoners to find fault with their monuments; and it is difficult to agree with the writer who described it as in its present position "adorning nothing, emphasising nothing, and by nothing emphasised." M. Gabriel Mourey, for instance, who, though a Frenchman, is also a lover of London, brings it very charmingly into his "impression" of the scene from Charing-Cross Bridge:

"I go every morning to Charing-Cross Bridge, to gaze on the 'magical effects' produced by fog and mist on the Thames. The buildings on the shores have vanished; there, where recently seethed an enormous conglomeration of roofs, chimneys, the perpetual encroachment of interminable façades, all that insentient life of stones,—heaped to lodge human toil, suffering, happiness,—seems to be now only a desert of far-reaching waters. The river has immeasurably widened, has extended its shores to the infinite. Such immensity is terrible ... the atmosphere is heavy; there (p. 39) is a conscious weight around, above, a weight that presses down, penetrates into ears and mouth, seems even to hang about the hair. We might, indeed, be existing in a kind of nothingness, except for the perpetual passage of trains—trains that shake the floor of the bridge, and jar our whole being with metallic vibrations.... The wooden sheds of the landing-stage, backed by the stone steps and parapet,—with, further on, the thin spire of Cleopatra's Needle, an unimagined network of lines,—appear suddenly out of nothingness; it might be a fairy city rising all at once; here are revealed the gigantic buildings of the Savoy Hotel, and yonder, farther on, those of Somerset House, as the fog gradually lifts; the whole effect is suggestive of a negative under the chemical action of the developer. There is, however, no distinctness; the negative is a fogged one; outlines are only distinguished with difficulty; and everything, in this strange and sad monochrome, seems to acquire a vast and altogether fantastic size. The sky, however, moves; thick, ragged clouds unravel themselves, in colour a dirty yellow fringed with white; they might well be great folds of torn curtains entangled in each other, curtains of dingy wadding, thickly lined, and edged with faint gold. But the light is too feeble to reflect itself, and the water below continues to flow dully, as though weighed down with the burden of that heavy sky; the pleasure-steamers, indeed, seem to cleave it with painful toil, to force a pathway, soon again closed; a pathway of which scarcely a trace remains, only a slow, sluggish undulation, soon lost in the general distracting cohesion of all and everything."

It may be interesting here to recall Lord Tennyson's sonnet, and the story told of it by his son:

"When Cleopatra's Needle was brought to London, Stanley asked my father to make some lines upon it; to be engraven on the base. These were put together by my father at once, and I made a note of them:

Cleopatra's Needle.

"Here, I that stood in On beside the flow

Of sacred Nile, three thousand years ago!—

A Pharaoh, kingliest of his kingly race,

First shaped, and carved, and set me in my place.

A Cæsar of a punier dynasty

Thence haled me toward the Mediterranean sea,

Whence your own citizens, for their own renown,

Thro' strange seas drew me to your monster town.

I have seen the four great empires disappear!

I was when London was not! I am here!"

The "Top" Season.

Waterloo Bridge, crossing the Thames at Somerset House, was built by Rennie in 1817. Canova considered it "the noblest bridge in the world, and worth a visit from the remotest corners of the earth." It was at first intended to call it the "Strand" Bridge; but it was eventually named "Waterloo," in honour of the victory just won. Yet Waterloo Bridge is not without its dismal associations. So many people, for instance, have committed suicide from it, that it has been called the "English Bridge of Sighs." It suggests Hood's ballad of the "Unfortunate":

"The bleak wind of March

Made her tremble and shiver:

But not the dark arch

Or the black flowing river."

(p. 41) Waterloo Bridge has indeed been the last resource of many an unhappy human moth—attracted by "the cruel lights of London"—to whom

"When life hangs heavy, death remains the door

To endless rest beside the Stygian shore."

Dante Rossetti, who painted his terrible picture of the lost girl found by her old lover on a London bridge at dawning, has well realised the ineffable sadness of the wrecks made by this whirlpool of London.

The Victoria Embankment, and indirectly also this splendid Waterloo Bridge, have given cause for one of the most eloquent diatribes of our greatest æsthetic critic. Mr. Ruskin, though he cannot but admire the vast curve of Waterloo Bridge, where the Embankment road passes under it, "as vast, it alone, as the Rialto at Venice, and scarcely less seemly in proportions," yet finds, in the wretched attempts at decoration on the Embankment, and in the sad want of "human imagination" of the English architect, windmills apt and ready to his lance. Unlike the Rialto, the "Waterloo arch," he remarks plaintively, "is nothing more than a gloomy and hollow heap of wedged blocks of blind granite":

"We have lately been busy," he says, "embanking, in the capital of the country, the river which, of all its waters, the imagination of our ancestors had made most sacred, and the bounty of nature most useful. Of all architectural features of the metropolis, that embankment will be, in future, the most conspicuous; and in its position and purpose it was the most capable of noble adornment. For that adornment, nevertheless, the utmost which our modern poetical imagination has been able to invent, is a row of gas-lamps. It has, indeed, farther suggested itself to our minds as appropriate to gas-lamps set beside a river, that the gas should come out of fishes' tails; but we have not ingenuity enough to cast so much as a smelt or a sprat for ourselves; so we borrow the shape of a Neapolitan marble, which has been the refuse of the plate and candlestick shops in every capital in Europe for the last fifty years. We cast that badly, and give lustre to the ill-cast fish with lacquer in imitation of bronze. On the base of their pedestals, toward the road, we put, for advertisement's sake, (p. 42) the initials of the casting firm; and, for farther originality and Christianity's sake, the caduceus of Mercury: and to adorn the front of the pedestals towards the river, being now wholly at our wits' end, we can think of nothing better than to borrow the door-knocker which—again for the last fifty years—has disturbed and decorated two or three millions of London street doors; and magnifying the marvellous device of it, a lion's head with a ring in its mouth (still borrowed from the Greek), we complete the embankment with a row of heads and rings, on a scale which enables them to produce, at the distance at which only they can be seen, the exact effect of a row of sentry-boxes."

Much, however, may be forgiven to Mr. Ruskin. On the other hand, the view from Waterloo Bridge is thus described by the late Mr. Samuel Butler: