OR

SPORTING CHAT AND SPORTING MEMORIES

STORIES HUMOROUS AND CURIOUS; WRINKLES OF THE FIELD

AND THE RACE-COURSE; ANECDOTES OF THE STABLE AND

THE KENNEL; WITH NUMEROUS PRACTICAL

NOTES ON SHOOTING AND FISHING

FROM THE PEN OF

VARIOUS SPORTING CELEBRITIES AND

WELL-KNOWN WRITERS ON THE TURF AND THE CHASE

EDITED BY

FOX RUSSELL

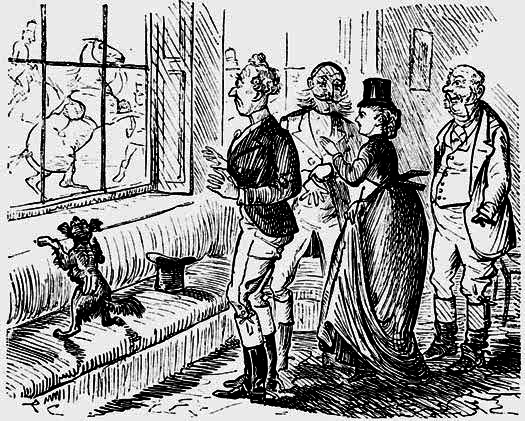

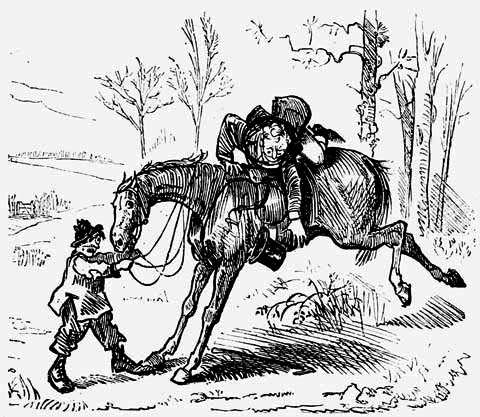

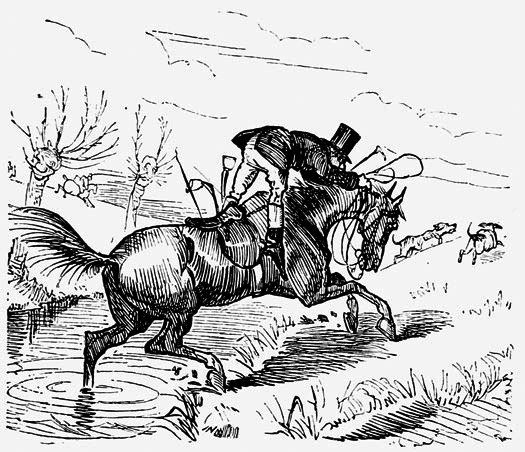

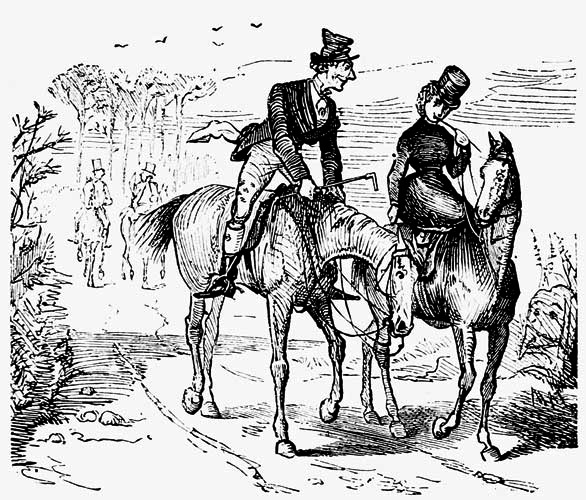

Illustrations by Randolph Caldecott.

IN TWO VOLUMES—VOL. I.

LONDON

BELLAIRS & CO.

1897

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| The Influence of Field Sports on Character | 1 |

| By Sir Courtenay Boyle | |

| Old-Fashioned Angling | 21 |

| By Captain R. Bird Thompson | |

| Partridge Day as it Was and as it Is | 36 |

| By "An Elderly Sportsman" | |

| Simpson's Snipe | 53 |

| By Terence le Smithe | |

| Podgers' Pointer | 80 |

| By Ben B. Brown | |

| The Dead Heat | 101 |

| By "Old Calabar" | |

| Only the Mare | 134 |

| By Alfred E. T. Watson | |

| Hunting in the Midlands | 155 |

| By T. H. S. Escott | |

| A Military Steeplechase | 171 |

| By Captain R. Bird Thompson | |

| How I Won my Handicap | 181 |

| Told by the Winner | |

| The First Day of the Season and its Results | 193 |

| By "Sabretache" | |

| A Day with the Drag | 210 |

| By the Editor | |

| Stag-Hunting on Exmoor | 221 |

| By Captain Redway | |

| Sport amongst the Mountains | 237 |

| By "Sarcelle" | |

| A Birmingham Dog Show | 251 |

| By "Old Calabar" | |

| Huntingcrop Hall | 268 |

| By Alfred E. T. Watson | |

| A Dog Hunt on the Berwyns | 286 |

| By G. Christopher Davies | |

| Some Odd Ways of Fishing | 298 |

| By G. Christopher Davies | |

| Shooting | 306 |

| By Captain R. Bird Thompson |

⁂ "The Dead Heat," by "Old Calabar," was originally contributed by the veteran sportsman to the pages of "Baily's Magazine," and is here reproduced by the permission of the Proprietors.

THE INFLUENCE OF FIELD SPORTS ON CHARACTER

Field sports have been generally considered solely in the light of a relaxation from the graver business of life, and have been justified by writers on economics on the ground that some sort of release is required from the imprisoned existence of the man of business, the lawyer, or the politician. Apollo does not always bend his bow, it is said, and timely dissipation is commendable even in the wise; therefore by all means, let the sports which we English love be pursued within legitimate bounds, and up to an extent not forbidden by weightier considerations.

But there seems to be somewhat more in field sports than is contained in this criticism. The influence of character on the manner in which sports are pursued is endless, and reciprocally the influence of field sports on character seems to deserve some attention. The best narrator of schoolboy life of the present day has said that, varied as are the characters of boys, so varied are their ways of facing or not facing a "hilly," at football; and one of the greatest observers of character in England has written a most instructive and amusing account of the way in which men enjoy fox-hunting. If, therefore, a man's character and his occupations and tastes exercise a mutual influence upon each other, it follows that while men of different dispositions pursue sports in different ways, the sports also which they do pursue will tell considerably in the development of their natural character.

Now, the field sport which is perhaps pursued by a greater number of Englishmen than any other, and which is most zealously admired by its devotees, is fox-hunting. It is essentially English in its nature.

"A fox-hunt to a foreigner is strange,

'Tis likewise subject to the double danger

Of falling first, and having in exchange

Some pleasant laughter at the awkward stranger."

And it is this very falling which adds in some degree to its popularity; suave mari magno, it is pleasant to know that your neighbour A.'s horse, which he admires so much, has given him a fall at that very double over which your little animal has carried you so safely; and it is pleasant to feel yourself secure from the difficulties entailed on B, by his desire to teach his four-year-old how to jump according to his tastes. But apart from this delight—uncharitable if you like to call it—which is felt at the hazards and failures of another, there is in fox-hunting the keenest possible desire to overcome satisfactorily these difficulties yourself. Not merely for the sake of explaining to an after-dinner audience how you jumped that big place by the church or led the field safely over the brook, though that element does enter in; but from the strong delight which an Englishman seems by birthright to have in surmounting any obstacles which are placed in his way. Put a man then on a horse, and send him out hunting, and when he has had some experience ask him what he has discovered of the requirements of his new pursuit, and what is the lesson or influence of it. He will probably give you some such answer as the following.

The first thing that is wanted by, and therefore encouraged by, fox-hunting, is decision. He who hesitates is lost. No "craner" can get well over a country. Directly the hounds begin to run, he who would follow them must decide upon his course. Will he go through that gate, or attempt that big fence, which has proved a stopper to the crowd? there is no time to lose. The fence may necessitate a fall, the gate must cause a loss of time, which shall it be? Or again, the hounds have come to a check, the master and huntsmen are not up (in some countries a very possible event), and it devolves upon the only man who is with them to give them a cast. Where is it to be? here or there? There is no time for thought, prompt and decided action alone succeeds. Or else the loss of shoe or an unexpected fall has thrown you out, and you must decide quickly in which direction you think the hounds are most likely to have run. Experience, of course, tells considerably here as everywhere; but quick decision and promptitude in adopting the course decided on will be the surest means of attaining the wished for result of finding yourself again in company with the hounds.

Further, fox-hunting teaches immensely self-dependence; every one is far too much occupied with his own ideas and his own difficulties to be able to give more than the most momentary attention to those of his neighbour. If you seek advice or aid you will not get much from the really zealous sportsman; you must trust to yourself, you must depend on your own resources. "Go on, sir, or else let me come," is the sort of encouragement which you are likely to get, if in doubt whether a fence is practicable or a turn correct.

Thirdly, fox-hunting necessitates a combination of judgment and courage removed from timidity on the one side and foolhardiness on the other. The man who takes his horse continually over big places, for the sake of doing that in which he hopes no one else will successfully imitate him, is sure in the end to kill his horse or lose his chance of seeing the run; and on the other hand, he who, when the hounds are running, shirks an awkward fence or leaves his straight course to look for a gate, is tolerably certain to find himself several fields behind at the finish. "What sort of a man to hounds is Lord A——?" we once heard it asked of a good judge. "Oh, a capital sportsman and rider," was the answer; "never larks, but will go at a haystack if the hounds are running."

It is partly from the necessity of self-dependence which the fox-hunter feels, that his sport is open to the accusation that it tends to selfishness. The true fox-hunter is alone in the midst of the crowd; he has his own interests solely at heart—each for himself, is his motto, and the pace is often too good for him to stop and help a neighbour in a ditch, or catch a friend's runaway horse. He has no partner, he plays no one's hand except his own. This of course only applies to the man who goes out hunting, eager to have a run and keen to be in at the death. If a man rides to the meet with a pretty cousin, and pilots her for the first part of a run, he probably pays more attention to his charge than to his own instincts of the chase; but he is not on this occasion purely fox-hunting; and, if a true Nimrod, his passion for sport will overcome his gallantry, and he will probably not be sorry when his charge has left his protection, and he is free to ride where his individual wishes and the exigencies of the hunt may lead him.

What a knowledge of country fox-hunting teaches! A man who hunts will, at an emergency, be far better able than one who does not to choose a course, and select a line, which will lead him right. Generals hold that the topographical instinct of the fox-hunter is of considerable advantage in the battle-field; and it is undoubtedly easy to imagine circumstances in which a man accustomed to find his way to or from hounds, in spite of every opposition and difficulty, will make use of the power which he has acquired and be superior to the man who has not had similar advantages.

Finally, fox-hunting encourages energy and "go." The sluggard or lazy man never succeeds as a fox-hunter, and he who adopts the chase as an amusement soon finds that he must lay aside all listlessness and inertness if he would enjoy to the full the pleasures which he seeks. A man who thinks a long ride to cover, or a jog home in a chill, dank evening in November, a bore, will not do as a fox-hunter. The activity which considers no distance too great, no day too bad for hunting, will contribute first to the success of the sportsman, and ultimately to the formation of the character of the man.

Fishing teaches perseverance. The man in Punch, who on Friday did not know whether he had had good sport, because he only began on Wednesday morning, is a caricature; but, like all caricatures, has an element of truth in it. To succeed as an angler, whether of the kingly salmon, or the diminutive gudgeon, an ardour is necessary which is not damped by repeated want of success; and he who is hopeless because he has no sport at first will never fully appreciate fishing. So too the tyro, who catches his line in a rock, or twists it in an apparently inexplicable manner in a tree, soon finds that steady patience will set him free far sooner than impetuous vigour or ruthless strength. The skilled angler does not abuse the weather or the water in impotent despair, but makes the most of the resources which he has, and patiently hopes an improvement therein.

Delicacy and gentleness are also taught by fishing. It is here especially that—

"Vis consili expers mole ruit suâ,

Vim temperatam di quoque provehunt in majus."

Look at the thin link of gut and the slight rod with which the huge trout or "never ending monster of a salmon" is to be caught. No brute force will do there, every struggle of the prey must be met by judicious yielding on the part of the captor, who watches carefully every motion, and treats its weight by giving line, knowing at the same time—none better—when the full force of the butt is to be unflinchingly applied. Does not this sort of training have an effect on character? Will not a man educated in fly-fishing find developed in him the tendency to be patient, to be persevering, and to know how to adapt himself to circumstances. Whatever be the fish he is playing, whatever be his line, will he not know when to yield and when to hold fast?

But fishing like hunting is solitary. The zealot among fishermen will generally prefer his own company to the society of lookers-on, whose advice may worry him, and whose presence may spoil his sport. The salmon-fisher does not make much of a companion of the gillie who goes with him, and the trouter does best when absolutely alone; and nothing is so apt to prove a tyrant, and an evil one, as the love of solitude.

On the other hand, the angler is always under the influence, and able to admire the beauties of nature. Whether he be upon the crag-bound loch or by the sides of the laughing burn of highland countries, or prefer the green banks of southern rivers, he can enjoy to the full the many pleasures which existence alone presents to those who admire nature. And all this exercises a softening influence on his character. Read the works of those who write on fishing—Scrope, Walton, Davy, as instances. Is there not a very gentle spirit breathing through them? What is there rude or coarse or harsh in the true fisherman? Is he not light and delicate, and do not his words and actions fall as softly as his flies?

Shooting is of two kinds, which, without incorrectness, may be termed wild and tame. Of tame shooting the tamest, in every sense of the word, is pigeon-shooting; but as this is admittedly not sport, and as its principal feature is that it is a medium for gambling, or, at least, for the winning of money prizes or silver cups, it may be passed over in a few words. It undoubtedly requires skill, and encourages rapidity of eye and quickness of action; but its influence on character depends solely on its essential selfishness, and the taint which it bears from the "filthy" effect of "lucre."

Other tame shooting is battue shooting, where luxuriously clad men, who have breakfasted at any hour between ten and twelve, and have been driven to their coverts in a comfortable conveyance, stand in a sheltered corner with cigarettes in their mouths, and shoot tame pheasants and timid hares for about three hours and a half, varying the entertainment by a hot lunch, and a short walk from beat to beat. Two men stand behind each sportsman with breech-loaders of the quickest action, and the only drawback to the gunner's satisfaction is that he is obliged to waste a certain time between his shots in cocking the gun which he has taken from his loader. This cannot but be enervating in its influence. Everything, except the merest action of pointing the piece and pulling the trigger, is done for you. You are conveyed probably to the very place where you are to stand; the game is driven right up to you; what you shoot is picked up for you; your gun itself is loaded by other hands; you have no difficulty in finding your prey; you have no satisfaction in outwitting the wiliness of bird or beast; you have nothing whatever except the pleasure—minimised by constant repetition—of bringing down a "rocketter," or stopping a rabbit going full speed across a ride.

The moral of this is that it is not necessary to do anything for yourself, that some one will do everything for you, probably better than you would, and that all you have to do is to leave everything to some person whom you trust. Or, again, it is, get the greatest amount of effect with the least possible personal exertion. Stand still, and opportunities will come to you like pheasants—all you have to do is to knock them over.

But it is not so with wild-shooting. Not so with the man, who, with the greatest difficulty, and after studying every available means of approach, has got within range of the lordly stag, and hears the dull thud which tells him his bullet has not missed its mark. Nor with him, who, after a hurried breakfast, climbs hill after hill in pursuit of the russet grouse, or mounts to the top of a craggy ridge in search of the snowy ptarmigan. Not so either with him, who traverses every bit of marshy ground along a low bottom, and is thoroughly gratified, if, at the end of a long day, he has bagged a few snipe; nor with him, who, despite cold and gloom and wet, has at last drawn his punt within distance of a flock of wild duck. In each of these, endurance and energy is taught in its fullest degree. It is no slight strain on the muscles and lungs to follow Ronald in his varied course, in which he emulates alternately the movements of the hare, the crab, and the snake; and it is no slight trial of patience to find, after all your care, all your wearisome stalk, that some unobserved hind, or unlucky grouse, has frightened your prey and rendered your toil vain. But, en avant, do not despair, try again, walk your long walk, crawl your difficult crawl once more, and then, your perseverance rewarded by a royal head, agree that deer-stalking is calculated to develop a character which overcomes all difficulties, and goes on in spite of many failures.

The same obstinate determination which is found in this, the beau ideal of all shooting, is found similarly in shooting of other kinds; and it is a question whether to the endurance inculcated by this pursuit may not be attributed that part of an Englishman's character which made the Peninsular heroes "never know when they were licked."

It is objected by foreigners to many of our national sports that they involve great disregard for animal life. "Let us go out and kill something," they say, is the exhortation of an Englishman to his friend when they wish to amuse themselves. Sport consists, they hold, in slaughter; sport therefore is cruel, and teaches contempt for the feelings of creatures lower than ourselves in the scale of existence. I do not wish to enter into this question, which has been a source of considerable controversy; but I would say three things in reference to it. First, that it is difficult to answer the question, Why should man be an exception to the rule of instinct—undoubtedly prevalent throughout the world—which leads every animal to prey upon its inferior? Secondly, that every possible arrangement is made by man for the comfort and safety of his prey—salmon, foxes, pheasants or stags—until the actual moment of capture, and that every fair chance of escape is given to it; and thirdly, that whatever the premises may be, the conclusion remains, that there is no race so far removed from carelessness of animal life and happiness as the English.

There are, however, other field sports which do not involve any destruction of life, and which, from the general way in which they are pursued, may fairly be called national. Foremost amongst these is racing.

Were racing freed from any influence, other than that which distinguished the races of past epochs, the desire of success; were the prize a crown of parsley or of laurel, and the laudable desire of victory the only inducement to contention, the effect on the men who are devoted to it could not be otherwise than for good. In modern racing, however, the element of pecuniary gain comes in so strongly, that the worst points of the human character are stimulated by it instead of the best, and the improvement of horseflesh and the breed of horses is sacrificed to the temporary advantage of owners of horses. To say, now, that a man is going on the turf, is to say, that he had almost be better under it; and though a few exceptional cases are found, in which men persistently keeping race horses have maintained their independence and strict integrity in spite of the many temptations with which they are assailed, yet, even they, have probably done so at the sacrifice of openness of confidence and perhaps of friendship. Trust no one is the motto of turfites. Keep the key of your saddle-room yourself; let no one, not even your trainer, see your weights. Pay your jockey the salary of a judge, and then have no security that he will not deceive you. The state of the turf is like the state of Corcyræa of old. Every man thinks, that unless he is actually plotting against somebody, he is in danger of being plotted against himself, and that the only safety he has lies in taking the initiative in deceit. The sole object is to win—

"Rem

Si possis recte, si non quocunque modo rem."

Take care you are not cheated yourself, and make the most of any knowledge of which you believe yourself to be the sole possessor.

What is the result of such a pursuit? what its moral? The destruction of all generosity, all trust in others, all large-mindedness: and the encouragement instead, of selfishness, of extravagance, and of suspicion.

The man whose friendship was warm and generous, who would help his friend to the limit of his powers, goes on the turf and becomes warped and narrow, labouring, apparently, always under the suspicion, that those whom he meets are trying, or wish to try, to get the better of him, or share, in some way, the advantages which he hopes his cunning has acquired for himself.

A thorough disregard for truth, too, is taught by horse-racing; not, perhaps, instanced always by the affirmation of falsehood, but negatively by the concealment or distortion of fact. An owner seldom allows even his best friend to know the result of his secret trials, and in some notable cases such results are kept habitually locked in the breast of one man, who fears to have a confidant, and doubts the integrity of everyone. Whether this is a state of things which can be altered, either by diminishing the number of race-meetings in England, or by discouraging or even putting down betting, I have no wish to consider; but that the present condition of horse-racing and its surroundings is very far removed from being a credit to the country, I venture to affirm.

Cricket is another field sport, the popularity of which has rapidly increased; partly from the entire harmlessness which characterises it, and leads to the encouragement of it by schoolmasters and clergymen, and partly from the fact that it is played in the open air, in fine weather, and in the society of a number of companions. I do not propose to inquire whether there is benefit in the general spreading of cricket through the country, or whether it may not be said that it occupies too much time and takes men away from other more advantageous occupations, or whether the combination of amateur and professional skill which is found in great matches is a good thing; but I wish, briefly, to point out one or two points in human nature which seem to me to be developed by cricket.

The first of these is hero-worship. The best player in a village club, and the captain of a school eleven, if not for other reasons unusually unpopular, is surrounded by a halo of glory which falls to the successful in no other sport. Great things are expected of him, he is looked upon with admiring eyes, and is indeed a great man. "Ah, it is all very well," you hear, "but wait till Brown goes in, Smith and Robinson are out, but wait till Brown appears, then you will see how we shall beat you, bowl him out if you can." His right hand will atone for the shortcomings of many smaller men, his prowess make up the deficiency of his side. Or look at a match between All England and twenty-two of Clodshire, watch the clodsmen between the innings, how they throng wonderingly round the chiefs of the eleven. That's him, that's Abel, wait till he takes the bat, then you'll "see summut like play." Or go to the "Bat and Ball" after the match, when the eleven are there, and see how their words are dwelt on by an admiring audience, and their very looks and demeanour made much of as the deliberate expressions of men great in their generation. Again, see the reception at Kennington Oval of a "Surrey pet" or a popular amateur, or the way in which "W. G." Grace is treated by the undemonstrative aristocracy of "Lord's," and agree with me that cricket teaches hero-worship in its full. What power the captain of the Eton or the Winchester eleven has, what an influence over his fellows, not merely in the summer when his deeds are before the public, but always from a memory of his prowess with bat or ball. There is one awkward point about this; there are many cricket clubs, and therefore many captains, and when two of these meet a certain amount of difficulty arises in choosing which is the hero to be worshipped. In a match where the best players of a district are collected, and two or more good men, known in their own circle and esteemed highly, there play together, who is to say which is the best; who is to crown the real king of Brentford? Each considers himself superior to the other, each remembers the plaudits of his own admirers, forgets that it is possible that they may be prejudiced, and ignores the reputation of his neighbour. The result is a jealousy among the chieftains which is difficult to be overcome, and which shows itself even in the best matches.

On the other hand, the effect of this hero-worship which I have described, is to produce a harmony and unity of action consequent on confidence in a leader which is peculiar to cricket. Watch a good eleven, a good university or public school team, and see how thoroughly they work together, how the whole eleven is like one machine, "point" trusting "coverpoint," "short slip" knowing that if he cannot reach a ball, "long slip" can, and the bowler feeling sure that his "head" balls, if hit up, will be caught, if hit along the ground, will be fielded. Or see two good men batting, when every run is of importance, how they trust one another's judgment as to the possibility of running, how thoroughly they act in unison. Such training as this teaches greatly a combination of purpose and of action, and a confidence in the judgment of one's colleagues which must be advantageous.

The good cricketer is obedient to his captain, does what he is told, and does not grumble if he thinks his skill underrated: the tyro, proud of his own prowess, will indeed be cross if he is not made enough of, or is sent in last; but the good player, who really knows the game, sees that one leader is enough, and obeys his orders accordingly.

There are other lessons taught by cricket, such as caution by batting, patience and care by bowling, and energy by fielding; but I have no space to dwell on these, as I wish to examine very briefly one more sport, which, though hardly national, is yet much loved by the considerable number who do pursue it. Boating is seen in its glory at the universities or in some of the suburbs of London which are situated on the Thames. It is also practised in some of the northern towns, especially Newcastle, where the Tynesiders have long enjoyed a great reputation.

By boating, I do not mean going out in a large tub, and sitting under an awning, being pulled by a couple of paid men or drawn by an unfortunate horse, but boat-racing, for prizes or for honour. The Oxford and Cambridge race has done more than anything to make this sport popular, and the thousands who applaud the conquerors, reward sufficiently the exertions which have been necessary to make the victory possible.

The chief lesson which rowing teaches is self denial. The university oar, or the member of the champion crew at Henley, has to give up many pleasures, and deny himself many luxuries, before he is in a fit state to row with honour to himself and his club; and though in the dramatist's excited imagination the stroke-oar of an Oxford eight may spend days and nights immediately before the race, in the society of a Formosa, such is not the case in real life. There must be no pleasant chats over a social pipe for the rowing man, no dinners at the Mitre or the Bull, no recherché breakfasts with his friends; the routine of training must be strictly observed, and everything must give way to the paramount necessity of putting on muscle. In the race itself, too, what a desperate strain there is on the powers! How many times has some sobbing oarsman felt that nature must succumb to the tremendous demand made on her, that he can go no further; and then has come the thought that others are concerned besides himself, that the honour of his university or his club are at stake, which has lent a new stimulus and made possible that final spurt which results in victory.

The habits taught by rowing, whether during training or after the race has commenced, lead to regularity of life, to abstemiousness, and to the avoidance of unwholesome tastes, and their effect is seen long after the desire for aquatic glory have passed away.

Such are some of the most prominent influences of English field sports, and as long as amusements requiring such energy, such physical or mental activity, and such endurance as fox-hunting, stalking, and cricket, are popular, there is little fear of the manly character of the English nation deteriorating, or its indomitable determination being weakened.

OLD-FASHIONED ANGLING

Angling is, I think, one of the most popular of British field sports; certainly, for one book written about any other kind, there must be half-a-dozen on the subject of fishing. I met lately with a most amusing old book on the "Art of Angling," published in 1801; and illustrated with very quaint old wood engravings of both fresh and sea water fish. It commences with a long anatomical and physiological description of fish, giving an account of their habits, method of feeding, &c. For this last the author draws considerably on his own imagination. For instance, he declares that mussels and oysters open their shells for the purpose of catching crabs, closing them when one creeps in, and thus securing their prey. The oyster also is declared to change sides with each tide, lying with the flat shell uppermost one time, and the convex the next. After this the author goes regularly through the alphabet, treating everything connected with fresh-water angling under its respective initial letter.

I suppose that at this time there were few, if any tackle shops, for most elaborate directions are given for making lines. These were to be of horse hair, and twisted in a "twisting instrument," whatever that was. The hair was to be with the top of one to the tail of the other, so that every part might be equally strong, and turned slowly, so as to allow it "to bed" properly; the different lengths were to be tied together either "by a water knot, or Dutch knot, or a weaver's." The line was to taper, beginning with three hairs down to a single one, where the hook was whipped on.

The rod, as a matter of the greatest importance, is duly treated. The wood was to be procured between the middle of November and Christmas Day; the stock or butt to be made of ground hazel, ground ash, or ground willow, not more than two or three feet long. The wood chosen to be that which shot directly from the ground—not from any stump—and every joint beyond was to taper to a top made preferably of hazel, though yew, crab, or blackthorn might be used. If it had any knots or excrescences, which were to be avoided if possible, they must be removed with a sharp knife. Five or six inches of the top were to be cut off, and a small piece of round, smooth, taper whalebone spliced on with silk and cobbler's wax, and the whole finished with a strong noose of hair to fasten the line to. This was for an ordinary rod; the best sort was made as follows:—A white deal or fir board, thick, free from knots, and seven to eight feet long, was to be procured, and a dexterous joiner was to divide this with his saw into several breadths; then with a plane to shoot them round, smooth, and rush-grown or taper. One of these would form the bottom of the rod, seven or eight feet long in the piece. To this was fastened a hazel six or seven feet long, proportioned to the fir; this also rush-grown, and it might consist of two or three pieces, to the top of which a piece of yew was to be fixed about two feet long—round, smooth, and taper; and, finally, a piece of round whalebone, five or six inches long. Some rings or eyes were to be placed on the rod in such a manner that when you laid your eye to one, you could see through all the rest. A wheel or winch must be fixed on, about a foot from the end of the rod, and, as a finish, a feather dipped in aqua fortis was passed over it, so as to make it a pure cinnamon colour. "This," the author adds, "will be a curious rod if artificially worked!"

The subject of fly-making, and how and when to use flies, is treated most exhaustively—no less than twenty-four pages being devoted to the subject. The materials named for fly-dressing are very good indeed, and very much the same as used now; but when the author tries to explain the actual method of using them he utterly fails. Anyone who attempted to tie flies in the way explained would produce most extraordinary specimens.

The author has taken very great pains, not only in naming the flies to be used each month, but the actual time of day for them, and the hours between which they must be used. Worms for bait are described and named with great exactness, and the best way to catch and keep them, also how best to scour them previous to use. I think, however, the method recommended for scouring one kind would be too much for any but a very enthusiastic angler—namely, to put them in a woollen bag, and keep them in your waistcoat pocket. Few persons could stand that, I think.

Many recipes for different sorts of pastes are given, but it is hard to believe that any fish would take them—"bean flour, the tenderest part of a kitten's leg, wax and suet beaten together in a mortar," scarcely sounds alluring; neither does a mixture of "fat old cheese (the strongest rennet), suet, and turmeric," appear to be very nice. To any of these pastes you may add "assafœtida, oil of polypody of the oak, oil of ivy, or oil of Peter." Well, I do not suppose that they would make much difference.

A great number of recipes for unguents, to smear over the worms used so as to make them more attractive, are given; and most extraordinary they are:—assafœtida, three drachms; camphire, one drachm; Venice turpentine, one drachm; beaten up with oils of lavender and camomile, is one recipe. Another is, "mulberry juice, hedgehog's fat, oil of water-lilies and oil of pennyroyal," mixed together; but the most elaborate one is as follows:—"Take the oils of camomile, lavender, and aniseed, of each a quarter of an ounce; heron's grease and the best of assafœtida, each two drachms; two scruples of cummin seed finely beaten to powder; Venice turpentine, camphire, and galbanum, of each a drachm; add two grains of civet and make into an unguent. This must be kept close in a glazed earthenware pot, or it loses much of its virtue; anoint your line with it and your expectation will be abundantly answered. Some anglers, however, place more confidence in a judicious choice of baits and a proper management of them, than in the most celebrated unguents." I think the concluding paragraph is delightful. I suppose it did at length dawn on the author's mind that people might object to carrying about such hideously stinking compositions.

The angler is told that "his apparel must not be of a light or shining colour, but of a dark brown, fitting closely to the body, so as not to fright the fish away." The impediments to our anglers' recreation are named. "The fault may be occasioned by his tackle, as when his lines or hooks are too large, when his bait is dead or decaying. If he angles at a wrong time of day, when the fish are not in the humour of taking his bait. If the fish have been frightened by him or with his shadow. If the weather be too cold. If the weather be too hot. If it rains much or fast. If it hails or snows. If it be tempestuous. If the wind blows high or be in the east or north. Want of patience and the want of a proper assortment of baits." Anglers are also warned "never to fish in any water that is not common without leave of the owner, which is seldom denied to any but those that do not deserve it." Another direction is given that would greatly horrify any Blue Ribbon army man who might see it, namely, "if at any time, you happen to be over-heated with walking or other exercise, you must avoid small liquors as you would poison, and rather take a glass of brandy, the instantaneous effects of which in cooling the body and quenching drought are amazing."

The laws as to angling and fishing generally are quoted at considerable length and seem most of them to be aimed at preventing immature fish being taken and preserves damaged. The penalties did not err on the side of clemency. By 5th Elizabeth, destroying any dam of any pond, moat or stew, &c., with intent to take the fish, was punished with three months' imprisonment and to be bound to good behaviour for seven years after; also by 21st Elizabeth, "no servant shall be questioned for killing a trespasser within his master's liberty who will not yield; if not done out of former malice. Yet if the trespasser kills any such servant it is murder."

I fancy the following, if carried out now, would rather astonish many fish dealers in the city of London:—"Those that sell, offer, or expose to sale or exchange for any other goods, bret or turbot under sixteen inches long; brill or pearl under fourteen; codlin twelve; whiting six; bass and mullet twelve; sole, plaice, and dab eight; and flounder seven, from their eyes to the utmost extent of the tail; are liable to forfeit twenty shillings, by distress, or to be sent to hard labour for not less than six or more than fourteen days, and to be whipped." I suppose most, if not all, of these enactments are now repealed, but if not, and they were enforced, a considerable sensation would be created by them.

One paragraph is very remarkable, as showing that over ninety years ago, the same views were promulgated, relating to the profit that might be obtained from fish in ponds, as have been brought forward in the Times and other papers during recent years. Our author says: "It is surprising that, considering the benefit which may accrue from making ponds and keeping of fish, it is not more generally put in practice. For, besides furnishing the table and raising money, the land would be vastly improved and be worth forty shillings an acre; four acres converted into a pond will return every year a thousand fed carp from the least size to fourteen or fifteen inches long, besides pike, perch, tench, and other fish. The carp alone may be reckoned to bring one with another, sixpence, ninepence, or perhaps twelvepence apiece, amounting at the lowest rate to twenty-five pounds, and at the highest to fifty, which would be a very considerable as well as useful improvement." Exactly; this has been written and pointed out in the papers year after year.

There are wood-cuts of every fish and full directions how to angle for them. For pike, trolling, live baiting, fishing with frogs, are all lengthily described; and also a curious sort of spinning, the motion being caused by cutting off one of the fins close to the gills and another behind the vent on the contrary side. I am sorry to say the author winds up by full directions for snaring and snatching.

It seems curious to be told that good places for roach fishing are by Blackfriars, Westminster and Chelsea Bridges, or by the piles at London Bridge; but that the best way by far was to go below the bridges and fasten your boat to the "stern of any collier or other vessel whose bottom was dirty with weeds," to angle there, as "you would not fail to catch many roach, and those very fine ones." The sailors on board colliers must have been a very different set in those days from what they are now. I fancy anyone trying to tie his boat to the stern of a collier, whether for fishing or any other purpose, would have a pretty hot time of it. The Thames, of course, is mentioned as one of the rivers where salmon were caught, though the localities are not named. Exact particulars are given for fishing for eels, but in those days they must have been a very amiable sort of fish, not at all like the obstinate and perverse creatures they are now, if they allowed themselves to be caught by sniggling in the way mentioned. You were to "get a strong line of silk and a small hook bated with a lob worm; next get a short stick with a cleft in it, and put the line into it near the bait; then thrust it into such holes as you suppose him to lurk in. If he is there, it is great odds that he will take it." The stick was then to be detached from the line and the eel allowed to gorge the bait. You were not to try and draw him out hastily, but to give him time to tire himself out by pulling. All I can say is, that if anyone ever managed to get an eel out in this way he must have had an uncommon share of luck. My own experience shows me that when an eel gorges your bait and gets into his hole, it is quite hopeless to attempt to get him out, and the only plan is to pull until something gives way, and that is never the eel, but usually your hook, and sometimes the line.

Our author having given every kind of advice and direction about angling, adds the following admonition:—"Remember that the wit and invention of mankind were bestowed for other purposes than to deceive silly fish, and that, however delightful angling may be, it ceases to be innocent when used otherwise than as a mere recreation"; and he winds up all he has to say about fresh-water angling thus:—"The editor having gone through the English alphabet, takes the liberty to tell gentlemen that the best way to secure fish is to transport poachers." A very wise piece of advice, no doubt much acted on in those days.

In the second part of the book, devoted to sea fish, no directions are given for fishing, but merely descriptions of them, and very curious some of these are. We are told of dolphins, that "they sleep with their snouts out of water," and that "some have affirmed that they have heard them snore; they will live three days out of water, during which time they sigh in so mournful a manner as to affect those with concern, who are not used to hear them."

Another fish, the "sea-wolf, taken off Heligoland, is a very voracious animal, and well furnished with dreadful teeth. They are so hard that if he bites the fluke of an anchor you may hear the sound and see the impression of his teeth." Certainly the engraving of it makes it an awful-looking thing, with a body like a codfish and an enormous head, with a huge mouth full of teeth like spikes. When the herring fishery is mentioned, it is curious that the author gives a full account of the Dutch fishery but passes over the English with a very brief notice. The account of the former is remarkable. Their vessels were a kind of barque called a buss, from forty-five to sixty tons burden, carrying two or three small cannon; none were allowed to steer out of port without a convoy unless they carried twenty pieces of cannon amongst them all. What can have been the use of this regulation I cannot imagine. A pirate would never attack a fishing-boat, and against a vessel of war they would have been useless. The regulations for fishing were very distinct. No man was to cast his net within 100 fathoms of another's boat; whilst the nets were cast, a light was to be left in the stern; if a boat was by any accident obliged to leave off fishing, the light was to be thrown into the sea, and when the greater part of the fleet left off fishing and cast anchor, the rest were to do the same.

Of the English fishery, the date of its commencement, the size of the nets and the names of the different sorts of herrings are merely given; these names are very curious, I wonder whether they are known on the coast now. Six sorts are given,—the Fat Herring, the largest and best; the Meat Herring, large, but not so thick as the first; the Night Herring, a middle-sized one; the Pluck, which has been hurt in the net; the Shotten Herring, which has lost its spawn; and the Copshen, which by some accident or other has been deprived of its head. When the whale fishery is mentioned, here too the description given relates entirely to the Dutch. As to the English it only says that in 1728 the South Sea Company began to work it with pretty good success at first, but that it dwindled away until 1740, when Parliament thought fit to give greater encouragement to it. The discipline in the Dutch whale fleet seems to have been very good; the following are some of the standing regulations:—In case a vessel was wrecked and the crew saved, the first vessel they met with was to take them in and the second half of those from the first, but were not obliged to take in any of the cargo; but if any goods taken out of such vessel are absolutely relinquished and another ship finds and takes them, the captain was to be accountable to the owner of the wrecked ship for one-half clear of all expenses. If the crew deserted any wrecked vessel, they would have no claim to any of the effects saved, but the whole would go to the proprietor. However, if present when the effects were saved and they assisted therein, they would have one-fourth. That if a person piked a fish on the ice, it was his own so long as he left anyone with it, but the minute he left it, the fish became the property of the first captain that came along. If it was fastened to the shore by an anchor or rope, though left alone it belonged to its first captor. If any man was maimed or wounded in the Service, the Commissioners of the Fishery were to procure him reasonable satisfaction, to which the whole fleet were to contribute. They likewise agreed to attend prayers morning and evening, on pain of a forfeit at the discretion of the captain; not to get drunk or draw their knives on forfeiture of half their wages, nor fight on forfeiture of the whole. They were not to lay wagers on the good or ill-success of the fishing, nor buy or sell with the condition of taking one or more fish on the penalty of twenty-five florins. They were likewise to rest satisfied with the provisions allowed them and never to light candle, fire, or match, without the captain's leave on the like penalty. These regulations were read out before the voyage commenced and the crew were then called over to receive the customary gratuity before setting out and were promised another on return in proportion to the success of the voyage. The vessels went north leaving Iceland on the left, to parallel 75°, but some, the author says, ventured as far as 80° or 82°. I fancy he had rather vague ideas on the subject of North latitude, as it was not until 1827 that Sir E. Parry reached 82°, the farthest point north ever attained up to that time.

Amongst other fish "stock fish" is mentioned, which is described as "cod fish caught in the North of Norway by fishermen who cut holes in the ice for the purpose. On hooking one, as soon as they pulled it out, it was opened, cleaned, and then thrown on the rocks where it froze and became as hard as a deal board, and never to be dissolved. This the sailors beat to pieces, often calling it fresh fish, though it may have been kept seven years and worms have eaten holes in it." But if the letter-press is curious, the engravings with which the book is illustrated are still quainter. The fish, whether minnows or salmon, reach the same length; the only difference being made in their breadth, even the whale is merely represented as rather thicker and with two little men with axes in their hands walking on it. The author undoubtedly took great pains in compiling his work, and in spite of all eccentricities there are many hints and suggestions that are useful even nowadays.

PARTRIDGE DAY AS IT WAS AND AS IT IS

By an Elderly Sportsman

The world advances—good. Having accepted which tenet, it would be unreasonable to deny that the pleasures and indulgences of the world advance also. Luxury is one of the pleasures and indulgences of the world. Therefore luxury advances. The syllogism is complete and sound; there is fault in neither major nor minor premiss; and we have therefore arrived at the ultimate conclusion that luxury is on the move—that is, has increased. I have seldom come across a more perfect illustration of my argument than in the early days of this month of September. I am not an old fogey; I do not set up pretensions to a claim for talking, with a kind of accompanying sigh, of the days "when I was a boy," when "we managed things so much better," &c., &c. Yet perhaps I am not exactly middle-aged either, and can at all events look sufficiently far back to note a material change in the manner in which old September is ushered in now as compared with its reception some years ago. There are probably few, who, if lacking experience of its pleasures, can duly appreciate the ardour with which a sportsman looks forward to the "glorious first." But let the appreciative observer note how manifestly that ardour has of late years abated. It has been my frequent custom ere autumn has made her final curtsey, to take up my quarters at the country house of a certain relative, and witness the unprovoked assault on, and reckless massacre of divers unoffending partridges in the ensuing month. The relative referred to is an elderly gentleman, and, in addition to the possession of lands of his own, and liberties to shoot over those of other people, is also the happy father of three stalwart sons, not to mention the complementary portion of the family with whom at present I have nothing to do. These three stalwart sons, beknown to me as mere brats, I have watched grow up with some interest, and that not only as regards their moral and intellectual training, but also as regards the physical culture of their frames, and the sporting bent of their mind. The youngsters were always fond of me. I have always been their fidus Achates, in their adventures by land and water, from teaching them to swim and row, down to setting night lines for eels, or traps for rats. Well do I recollect arriving, on the evening of the 31st of August, some years ago, at the old place in Lincolnshire, and finding all three in a state of wild exuberance of spirits in anticipation of the morrow's sport; Jack, the eldest, just then promoted to a gun of his own, of which he was enormously proud, and the other two contenting themselves with the exciting prospect of plodding after us the whole day in the hopes of being allowed to let off our charges at its conclusion. Everybody was eager enough then, and the Squire after an evening spent—much to the disgust of the ladies—in discussing the all-engrossing topic of "the birds," sends us off early to bed, that we may all be up betimes in the morning.

We wake at seven, or rather are awoke, for the boys have been up since five, "chumming" (I know no word so appropriate) with the keepers; and even the Squire himself overhead I have heard stamping across his room to look out at the weather several times since four o'clock. We are awoke, then, at seven, and ere we have had time to take that fatal turn, the sure forerunner of a second sleep, a knock, or rather a thunderclap, is heard on the outer panels of the door, and Uncle Sam (they always call me Uncle Sam, though I am not their uncle, and my name is not Samuel) is summoned to "look sharp, and dress." Too cognizant of the fact that Uncle Sam's only chance of peace is to obey, we splash into our tub forthwith, encase our person in an old velveteen and gaiters, and having gulped our coffee and hastily devoured our toast, find ourself at nine o'clock standing on the hall steps, and comparing guns with Jack, previous to a start for the arable. Two keepers, a brace of perfect pointers, and a retriever, are awaiting, even at that hour, impatiently, our departure for the scene of action.

Two miles' walk in the soft September air serves to brace our nerves for the work before us; and the head keeper and the Squire having conferred together like two generals, on our arrival at the seat of war, we at length find ourselves placed—I should perhaps rather say marshalled—in the turnips and ready for the fray. What a picture it is! how truly English! each sportsman's eye glistening with excitement and pleasure, as he poises his gun, each in his own readiest manner and favourite position, the Squire casting his eye along the line with the careful scrutiny of a field-marshal examining his forces previous to a final and decisive struggle; the two pointers, too well disciplined to show their ardour in gestures, standing mute behind the keeper; Jack with his gun full-cocked and ready to fire almost before the quarry is started; and his two brothers bursting with excitement, talking in hurried and ceaseless whispers behind the back of Uncle Sam, bearing no distant resemblance, as far as their half-checked ardour is concerned, to the brace of pointers behind the keeper. But there is no time for indulging in reverie as to the scene; a low "Hold up, then!" is heard from the head-keeper, the two graceful dogs bound forward, the line advances, and the action has commenced. A rabbit starts from under Jack's feet: Bang!—and the shot enters a turnip, a yard behind the little white stern hopping and popping to his burrow, despite the reiterated assurances of Master Jack that he is hit, and who forgets to reload accordingly. "Hold up!" to the crouching pointers, and away we move again, watching the graceful movements of the dogs as they work the field before us. Rake, a young dog in his first season, is breaking a little too much ahead; but ere the keeper's "Gently, boy!" had reached him, he has suddenly pulled up, and, with tail stiff and leg up, is standing, motionless as a statue, over a covey. We advance, in the highest excitement:—whirr! goes bird after bird almost singly; and our first covey of the season leaves two brace and a half on the field. One o'clock comes; we have steadily beaten turnips and stubble, clover and mustard, and we spy a man with a donkey and panniers on the brow of the hill in front of us. We beat up to him, bagging a hare and a single bird on our way, and during the half-hour that is allowed us for our bread and cheese and one glass of sherry, we enjoy to our heart's content the large delights of loosing our tongues, after several hours' rigid silence. But "time is up," and we are again on the move till six; we are tired, but we don't know it; we are hungry and thirsty, but we feel not their pangs, till, with our five-and-twenty brace behind us in the bags, we strike across the park on our homeward journey. Uncle Sam's gun is yielded up to Master Tom to let off the charge with the shot drawn; but he manages surreptitiously to obtain our shot-flask, and joins us on the hall steps with a dead rabbit, somewhat mauled, however, from the young rascal's having fired at it at ten paces. We sit down to dinner in high good-humour:—who is not, after a good day? We defend our sport before the ladies from the charge of cruelty, and retire to roost so tired that we take the precaution to lock our door, to prevent the too early and too sure incursion of the young Visigoths in the morning. Alas! for the days that are no more. Seven or eight years have passed since that pleasant day, and Downcharge Hall again welcomes Uncle Sam on the evening of the 31st, under its hospitable roof; I find the boys all grown into young men; Jack is a captain of Hussars, Tom is a subaltern in the Engineers, and Dick has just left Christ Church. They are still as fond as ever of Uncle Sam, though they occasionally venture so far nowadays, as to offer an opinion adverse to his on sporting matters, in which his word was formerly supreme. As I descend to dinner, I pass Jack's room. Hailed by its tenant, of course. I enter, and find him occupied, with care above his years, in the adjustment of his spotless white necktie, two of which articles, crumpled too much in the operation, are at present adorning the floor. "Think of shooting to-morrow, Sam?" (The title of "uncle" has been dropped since Jack first stroked his downy upper lip as a second lieutenant). I stand aghast. Here is a young man, full of health and vigour, on the evening of the 31st August, questioning a fellow-man, who has just travelled some hundred miles and more to Downcharge Hall, with his arm round his gun-case, as to his intention of shooting on the 1st of September. Entertaining a faint hope that, in the exuberance of his youthful spirits, he may be chaffing his old relative, I gasp out an affirmative, and, obeying the summons of the dinner-bell, descend the stairs. There is a large party of guests, but dinner proceeds with but one allusion to the morrow and that is from Dick, who exclaims, as he fingers the delicate stem of his champagne glass, "By-the-by, to-morrow will be the 1st." The piece of fowl I was that moment in the act of swallowing stuck in my throat; my appetite was destroyed, and I silently, but sorrowfully, resolved that for the future no prodigy could have power to amaze me. Our guests stayed late, and at half-past eleven o'clock, mindful of my early rising the next day, I began to grow fidgetty. By twelve o'clock, however, they had all gone; and having despatched the ladies of the house to bed, my hand was already grasping my bed-candle, when Tom arrested my intention, bidding me, in a voice of manifest astonishment at what he was pleased to call my "early roost," to come and do a pipe or two first in Dick's room. Labouring under the delusion that a quarter of an hour was about to be devoted to arranging our sporting plans, I obeyed, and after two hours in Dick's room, spent almost entirely in discussing the relative merits and demerits of certain ladies and horses, found myself between the sheets at last. Awaking with a start, in the morning, to discover it is eight o'clock, I dress with all possible speed, haunted the while with terrible pictures of impatient sportsmen below anathematizing my tardiness as they wait breakfast for me. I hurry down stairs,—the breakfast room is tenantless. My first impression is that they have been unable to curb their sporting ardour, and have started without me. Hearing a footstep on the gravel sweep without, I step through the open casement, and confront a pretty dairymaid bringing in the milk and cream for breakfast.

"Fine mornin', sir."

"Yes. Which way have they gone—can you tell me?"

"Same gait as ever, sir. Joe have druv 'em down agin the fenny pasture, arter milkin' up hinder."

"Ah! but the gentlemen, not the cows."

"The gentlemen, is it? Maybe if ye look in their beds ye'll see 'em this time o' day."

Heaving a mighty sigh, I leave the dairymaid, and stroll up and down the garden, listening with increasing impatience to the distant call of the partridges in the park. Nature at Downcharge Hall that morning was at all events beautifully still; there was a slight mist, too, gradually clearing off from the distance, which betokened very surely a broiling day, and made me long the more to get our seven or eight brace before the mid-day heat should come upon us. My longings and reflections, however, were suddenly cut short by a pitying butler, who had brought me out the Times, with the remark that "Master and the young gentlemen seldom has their breakfasts before ten." This was cheerful; however, I consoled myself with the paper, and just as I had finished discovering who was born, married, or dead, and had commenced reading the entreaties to return to afflicted initial letters, &c., &c., Dick's terrier entered the room, the forerunner of his master, who, remarking on my actually being an earlier bird than himself, was followed, in the course of about twenty minutes, by the others.

"I suppose we shoot to-day: where shall we begin?" asks Tom.

"Oh! we will shoot up from Brinkhill," answers the Squire.

"Brinkhill—two miles;—must have a trap," says Jack.

The two-mile walk used to be part of the order of the day; it gave us a little time for conversation, prohibited from its conclusion till lunch; it braced one up, and made one, in sporting phraseology, "fit"; but nowadays a carriage is necessary, and the young Nimrod is unequal to any fatigue beyond that which he must necessarily undergo in pursuit of his game. However, we are late, so I can't object to it; and, burning my throat in my hasty disposal of my second cup of coffee, I rush upstairs to get ready my trusty Westley Richards, which, by the way, is a muzzle-loader, yet does not take so long to load as to require a man behind me with a second gun. Five minutes, and fully equipped I re-enter the breakfast-room, where I am astonished to find my "get-up" creates unfeigned amazement.

"What! ready now!" says Tom; "what's the use of being in such a hurry?—let's do a pipe and a game of billiards first."

"Ah, by-the-by," adds Dick, "what time shall we start? Better have the trap at twelve—quite early enough, eh?"

So Jack betakes himself to the newspaper; I am dragged off in disgust to the billiard-room; and the Squire goes off to show old Jones, who is staying here, all about the gardens, &c.

How I loathe the gardens from that moment!—how every shrub became a bugbear, every flower a poisonous weed, to my jaundiced eye, as I mentally abused my host for not turning out everybody sooner, and doing things smarter! My temper is rapidly vanishing; I have been beaten in two games by Tom, to whom I used formerly to allow fifteen out of fifty; I am smoking a cigar of Dick's (a bad one I think it, of course), when suddenly the sound of wheels breaks on my ear, and rushing madly to my room again, I don my shot-belt, I pocket wads, powder, and caps, shoulder my gun, and in two minutes am seated in the elegant little double dog-cart, waiting in a broiling sun for these tardy sportsmen. I have sat for full a quarter of an hour, when Jack strolls out, and, in a voice as though nothing had or was about to happen, exclaims—

"Hallo, Sam! are you ready? I must go and dress." And this to a man who has been gaitered since half-past eight. At half-past twelve he reappeared, dressed in magnificent apparel, the result of Poole's and Anderson's united efforts, and examining, to the increase of my impatience, the elaborate locks of a brand new breech-loader. Formerly, we used to take care of that sort of thing the night before at the latest. However, our horses are good ones, and Dick, who knows very well how to handle them—about the only thing I can say for him—puts them along in very neat form at a brisk pace to Brinkhill. This is all very pleasant; and as we near the ground my spirits begin to rise again. It takes us, however, at least twenty minutes to discuss which is the most advantageous beat—a matter which used to be settled as we came along; but I am at last on the move, and begin to forget the past grievances, only hoping they won't strike work too early. It is the same old field in which I so well remember Jack making his debût and missing the rabbit; but I miss the eager faces of those days sadly; it doesn't seem the same thing to me; half the pleasure of a thing, after all, is in enjoying it in company; but that half is sadly marred if the said company are cool in their enjoyment. The dogs, too, are disgustingly wild now. Old Rake breaks fence and flushes our first covey long out of gunshot, my disgust at which is further augmented by one of the keepers, as wild as the dog, breaking line and starting a hare, as remote as the partridges, by his loud imprecations after the miscreant, who is utterly deaf alike to whistle, threats, and entreaties. There is fault enough here; but it doesn't lie entirely with the keeper; it is too evident there is an absence of the eye of the master. If the Squire grows indifferent to their proceedings, he can scarcely expect his dogs and keepers to be what they were; the keeper gets lazy or dishonest, the dogs' training is neglected, and by-and-by they become useless or worse than useless, and their services are discarded. Now if there is one thing more than another which enhances the pleasure of a day's partridge-shooting, it is to watch a brace of well-trained pointers work a field. Why is it then—for obviously it is so—that the use of dogs, and especially of setters and pointers in the field, is gradually being discarded?

But to proceed. As soon as order is tolerably restored, we advance again, and pretty steadily beat two or three fields, bagging, with an unheard-of amount of missing, about two brace of birds. We are just entering the next field, when the Brinkhill tenant rides up and asks us all in to lunch. Ye gods, what a feast! Some years ago some bread and cheese, and perhaps a couple of glasses of sherry under a hedge was considered ample on these occasions. Now, however, I have before me an elegant repast of ham and tongue, of fowls and lamb, of pies and fruit, of beer and sherry, port and claret, such as would have shamed the epicurean deities of heathen mythology quaffing ambrosial nectar on the heights of Olympus. With a hopeless shudder I deposit my gun in a corner of the room and take my seat. We breakfasted at ten, but the "unwonted" exercise (alas! it should be so) has given the youngsters an appetite, and their tongues are tied for ten minutes, before worthy Mr Shorthorn, the tenant, produces a bottle of "that very fine old port" he so wishes the Squire to taste. I am not exaggerating when I state that lunch lasted a good hour. Then his pigs are inspected, and what with the wine and the waiting, I can well foresee what will happen to our sport: tongues will be loosed; misses will, if possible, increase; and I feel convinced that the partridges will have little to fear from us for this afternoon, at all events. However, we do manage at last to get away by about half-past three or four o'clock, and commence beating a very promising piece of stubble. I have just bagged a hare, and the dogs have been reduced, by dint of much rating, into a state of downcharge whilst I load, when something is heard galloping behind us, and Dick, who had stayed behind, as we thought, to fill his powder-flask, appears in the field trying the paces of the tenant's young one. Although he is well behind the beat, the galloping horse forms a disturbing element to the guns. Dick rides over the low fence at the end, round the next field, and finally returns right in the way of a shot I might have had at a landrail. I don't swear, because I don't approve thereof, and, moreover, am moderate in my temper; but this is indeed trying, and, to make matters worse, the fellow doesn't appear in the least bit ashamed of himself, but quietly dismounts, feels the legs of the colt carefully down, and, refusing to take his gun from the keepers, remarks that he is tired of missing, and (to my joy) shall go home. A prudent resolve, as he had fired at least twenty or thirty shots without touching a feather, as it seemed to my heated imagination; but the keeper, with a presence the late Duc de Morny might have envied, urges him "not to give over yet; he might 'ave a haccident and hit summut." Laughter is irresistible, but Dick's ardour is not equal to trusting to this remote contingency, so he wends his way homewards, for a wonder, on his own legs. The rest of us proceed again, but the shooting is, if possible, worse than before lunch; and as we enter the park again I ask, in a dejected tone of the head keeper, "What is the bag?" "Seven brace, three hares, and one rabbit." I turn away with a sigh, and mentally resolve to remove from my head, in the solitude of my chamber, on my return, the hairs—the many hairs—that must have turned grey during that terrible day; and I join the rest to reseek the hall, a sadder and a sulkier man. We enter the billiard-room at six, to find Dick engaged in a game of billiards with his pretty cousin, Lucy Hazard—the dog! but feeling that he deserves nothing at our hands, we break the tête-à-tête and summon the other ladies for a pool. Lucy has been chaffing Master Dick about "being such a muff as to return so soon." Quite right—an uncommonly nice girl is Miss Lucy, and with £50,000 of her own, too, they say. If I were ten years younger, I think I would marry her (I am far too vain to doubt her consent), and get some shooting of my own,—some shooting, sir, conducted on my own principles: I don't care much for the Downcharge Hall style of doing business. "C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre," remarked a French general, as he levelled his glass at our light squadrons charging through the bloody vale of Balaklava. "C'est luxurieux, mais ce n'est pas le sport," remarks the writer of this grumble, as he levels his pen at the sportsmen of Downcharge Hall and all who may resemble them.

SIMPSON'S SNIPE

"Who is Mr Simpson?" asked my wife, tossing a letter across the breakfast-table. This same little lady opens my correspondence with the sang-froid of a private secretary.

"Who is Mr Simpson?" she repeated. "If he is as big as his monogram, we shall have to widen all the doors, and raise the ceilings, in order to let him in."

The monogram referred to resembled a pyrotechnic device. It blazed in all the colours of the rainbow, and twisted itself like the coloured worsted in a young lady's first sampler.

"Simpson," I replied, in, I must confess, a tremulous sort of way, "is a very nice fellow, and a capital shot."

"I perceive that you have asked him to shoot."

"Only for a day and a night, my dear."

"Only for a day and a night! And where is Willie to sleep, and where is Blossie to sleep? You know the dear children are in the strangers' rooms for change of air, and really I must say it is very thoughtless of you;" and my wife's nez retroussé went up at a very acute angle, whilst a general hardness of expression settled itself upon her countenance, like a plaster cast.

I had a bad case. I had been dining with a friend, my friend Captain de Britska. I had taken sherry with my soup, hock with my fish, champagne with my entrée, and a nip of brandy before my claret. What I imbibed after the Lafitte I scarcely remember. Mr Simpson was of the party, and sat next to me. He forced a succession of cigars into my mouth, and subsequently a mixture of tobacco, a special thing. (What smoker, by the way, hasn't a special thing in the shape of a mixture? what gourmet has no special tip as regards salad-dressing?) We spoke of shooting. He asked me if I had any. I replied in the affirmative, expressing a hope that he would at some time or other practically discuss that fact. Somehow I was led into a direct invitation, and this was the outcome. I had committed myself beneath my friend's mahogany, and under the influence of my friend's generous wine. I was in a corner; and now, ye gods! I had to face Mrs Smithe. There are moments when a man's wife is simply awful. Snugly entrenched behind the unassailable line of defence, duty, and with such "Woolwich Infants" as her children to hurl against you, which she does in a persistent remorseless way, she is a terror. No man, be he as brave as Leonidas or as cool as Sir Charles Coldstream, is proof against the partner of his bosom when she is on the rampage; and, as I have already observed, Mrs S. was "end on."

"Another change will do the children good, Maria," I observed.

"Yes, I suppose so. It will do Willie's cold good to sleep in your dressing-room without a fire, won't it? and Blossie can have a bed made up in the bath. Is this Mr Simpson married or single?"

Hinc illæ lachrymæ. I couldn't say. I never asked him.

"What does it matter?" I commenced, with a view to diplomatising.

"Yes, but it does," she interposed. "If he is a respectable married man, which I very much doubt, he must have dear Willie's room."

"I am very sorry that I asked him at all, Maria; but as he has been asked, and as I must drive over to meet him in a few minutes, for Heaven's sake make the best of it."

"Oh, of course; I receive my instructions, and am to carry them out. All the trouble falls upon me, while you drive off to the station smoking a shilling cigar, when you know that every penny will be wanted to send Willie to Eton."

I got out of it somehow. Not that Mrs S. was entirely pacified. She still preserved an armed neutrality; yet even this concession was very much to be coveted. She's a dear good little creature, but she has fiery moods occasionally; and I ask you, my dear sir, is she one whit the worse for it? How often does your good lady fly at you during the twenty-four hours? How often! The theme is painful. Passons.

My stained-wood trap was brought round by my man-of-all-work, Billy Doyle. Billy is a tight little "boy," over whose unusually large skull some fifty summers' suns have passed, scorching away his shock hair, and leaving only a few streaks, which he carefully plasters across his bald pate till they resemble so many cracks upon the bottom of an inverted china bowl. Billy is my factotum. He looks after my horse, dogs, gun, rod, pipes, and clothes, with a view to the reversion of the latter. He was reared, "man an' boy," on the estate, and is upon the most familiar yet respectful terms with the whole family. Billy continually lectures me, imparting his opinions upon all matters appertaining to my affairs, as though he were some rich uncle whose will in my favour was safely deposited with the family solicitor.

"We've twenty minutes to meet the train, Billy," I observed, giving the reins a jerk.

"Is it for to ketch the tin-o'clock thrain from Dublin?" he asked.

"Yes."

"Begorra, ye've an hour! She's like yourself—she's always late."

"There's a gentleman coming down to spend the day and shoot," I said, without noticing Billy's sarcasm.

"Shoot! Arrah, shoot what?"

"Why, snipe, plover—anything that may turn up."

"Be jabers, he'll have for to poach, thin."

"What do you mean, Billy?"

"Divvle resave the feather there is betune this an' Ballybann; they're dhruv out av the cunthry."

"Nonsense, man. We'll get a snipe in Booker's fields."

"Ye will, av ye sind to Dublin for it."

I felt rather down in the mouth, for I had during the season given unlimited permission to my surrounding neighbours to blaze away—a privilege which had been used, if not abused, to the utmost limits. Scarce a day passed that we were not under fire, and on several occasions were in a state of siege, in consequence of a succession of raids upon the rookeries adjoining the house.

"We can try Mr Pringle's woods, Billy."

"Yez had betther lave thim alone, or the coroner 'ill be afther havin' a job. Pringle wud shoot his father sooner nor he'd let a bird be touched."

"This is very awkward," I muttered.

"Awkward! sorra a shurer shake in Chrisendom. It's crukkeder nor what happened to ould Major Moriarty beyant at Sievenaculliagh, that me father—may the heavens be his bed this day!—lived wud, man an' boy."

Billy was full of anecdote, and being anxious to pull my thoughts together, I mechanically requested him to let me hear all about the dilemma in which the gallant Major had found himself.

"Well, sir, th' ould Major was as dacent an ould gintleman as ever swallied a glass o' sperrits, an' there was always lashins an' lavins beyant at the house. If ye wor hungry it was yerself that was for to blame, and if ye wor dhry, it wasn't be raisin av wantin' a golliogue. Th' ould leddy herself was aiqual to the Major, an' a hospitabler ould cupple didn't live the Shannon side o' Connaught. Well, sir, wan mornin' a letther cums, sayin' that some frind was comin' for to billet on thim.

"'Och, I'm bet!' says the Mrs Moriarty.

"'What's that yer sayin' at all at all?' says th' ould Major; 'who bet ye?' says he.

"'Shure, here's Sir Timothy Blake, and Misther Bodkin Bushe, an' three more comin',' says she, 'an' this is only Wednesday.'

"'Arrah, what the dickens has that for to say to it?' says the Major.

"'There's not as much fresh mate in the house as wud give a brequest to a blackbird,' says she; 'an' they all ate fish av a Friday, an' how are we for to get it at all at all? An' they'll be wantin' fish an' game.'

"Ye see, sir," said Billy, "there was little or no roads in thim ould times, an' the carriers only crassed that way wanst a week."

"'We're hobbled, sure enough,' says the Major, 'we're hobbled, mam,' says he, 'an' I wish they'd had manners to wait to be axed afore they'd come into a man's house,' he says.

"'Couldn't ye shoot somethin'?' says Mrs Moriarty.

"'Shoot a haystack flyin', mam,' says the Major, for he was riz, an' when he was riz the divvle cudn't hould him; 'what is there for to shoot, barrin' a saygull? an' ye might as well be aitin' saw-dust.'

"'I seen three wild duck below on the pond,' she says.

"'Ye did on Tib's Eve!' says the Major.

"'Och, begorra, it's thruth I'm tellin' ye', says she; 'I seen thim this very mornin', when I was comin' from mass—an' be the same token,' says she, lukkin' out av the windy, 'there they are, rosy an' well.'

"'Thin upon my conscience, mam,' roared the Major, 'if I don't hit thim I'll make them lave that!'

"So he ups an' loads an ould blundherbuss wud all soarts av combusticles, an' down he creeps to the edge av the wather, and hides hisself in some long grass, for the ducks was heddin' for him. Up they cum; an' the minnit they wor within a cupple av perch he pulls the thrigger as bould as a ram, whin by the hokey smut it hot him a welt in the stummick that levelled him, an' med him feel as if tundher was inside av him rumblin'. He roared millia murdher, for he thought he was kilt; but howsomever he fell soft an' aisy, an' he put out his hand for to see if he was knocked to bits behind, whin, begorra, he felt somethin' soft an' warm. 'Arrah, what the puck is this?' sez he; an' turnin' round, what was he sittin' on but an illigant Jack hare. 'Yer cotch, ma bouchal,' sez he; 'an' yer as welkim as the flowers o' May.'

"Wasn't that a twist o' luck, sir?" asked Billy pausing to take breath.

"Not a doubt of it. But what became of the ducks?"

"Troth, thin, ye'll hear. The Major dhropped two av thim wud the combusticles in the blundherbuss, but th' ould mallard kep' floatin' on the wather in a quare soart av a way, an' yellin' murdher. When the Major kem nigh him, he seen that he was fastened like to somethin' undher the wather; an' whin he cotch him, what do you think he found? It's truth I'm tellin' ye, an' no lie: he found the ramrod, that he neglected for to take out o' the gun, run right through th' ould mallard. Half av it was in the mallard, an' be the hole in me coat, th' other half was stuck in a lovely lump av a salmon; and the bould Major cotch thim both. 'Now,' says he, 'come on, Sir Tim an the whole creel of yez, who's afeard?' An' I'm just thinkin' sir," added Billy, as we dashed into the railway yard, "that if ye don't get a slice av luck like Major Moriarty's, yer frind might as well be on the Hill o' Howth."